The Screen as a Spectacle

“A screen is a barrier,” wrote the philosopher Stanley Cavell in 1971. “What does the silver screen screen? It screens me from the world it holds—that is, screens its existence from me.” (Cavell, S. cited in Mondloch, K. 2007, p.21)

This essay will focus mainly on screens used in media installation art in museums and gallery spaces, briefly touching on the impact that screens have on society outside of artistic institutions. I will focus on screens as a masterful part of today’s visual culture and a more ‘ambivalent’ object than we may give them credit for. I will be focusing specifically on works by artists Robert Whitman, Bruce Nauman, Nam June Paik and finally Eija-Liisa Ahtalia and how they have made a significant impact on the interaction between viewer and screen-based works today.

Media screens initially started making an introduction into art galleries as early as the late 1950s. “Artists were newly concerned with the viewer-screen interface itself: the multifarious physical and conceptual points at which the observing subject meets the media object.” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.2) There is much to be said, not only of the integration of screens into art institutions but also of the increase in everyday use of screens in modern day society and how they so drastically change how we interact with the world.

“Broadly speaking, interface means the communication boundary or point of interaction between two other parts or systems, while it becomes part of that system, influencing how two parties interplay with each other” (Jeong, S. 2013, p.3)

Screens exist in our everyday lives way beyond our phones, laptops, or cameras and even though it is a word that has crept into our everyday vocabulary, we all still struggle to define it. Professor of Media Studies, Charles Acland describes:

Screens exist in our everyday lives way beyond our phones, laptops, or cameras and even though it is a word that has crept into our everyday vocabulary, we all still struggle to define it. Professor of Media Studies, Charles Acland describes:

"Defining a screen is baffling, precisely because it is not in and of itself a medium, format, or platform. Rather, it is a combination of all three, one that materializes how we come to see and describe the differences and connections among television, film, computers, electronic signage, and digital spaces" (Acland, C. 2012, p.168)

Mondloch in her account of ‘viewing media installation art’ pushes our understanding of a screen way beyond our original thinking. “Almost anything - glass, architecture, three-dimensional objects, and so on - can function as a screen and thus a connective interface to another (virtual) space.” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.2) What Mondloch does here is acknowledge the spatiality of a screen in gallery spaces, allowing us to think of them as material and immaterial objects at the same time. Honing in on the kind of spectatorship that these ‘screen-reliant’ installations evoke, our thinking changes from a screen being something we just look at, to something that we are actually able to look through. (Mondloch uses the term ‘screen-reliant’ as opposed to ‘screen-based’ to signify the performative aspect of a screen.)

“The screen then is a curiously ambivalent object - simultaneously a material entity and a virtual window, it is altogether an object which, when deployed in spatialized sculptural configurations, resists facile categorization.” (Mondloch, 2010, pg.2)

The integration of screens into museums and art galleries has certainly been a huge factor in how abundant these interfaces have become in modern society but Mondloch makes a point of acknowledging that this is by no means the initial way in which interaction between interface and viewer/observer has been created.

“Two-dimensional representations, such as perspectival systems, maps, and x-rays, have unquestionably been employed to affect reality from a distance before the development of digital media. Any fervent assertions about the novelty of the ‘interactivity’ or ‘virtuality’ that are commonly attributed to digital art should, therefore, ring hollow.” (Mondloch, K, 2010, p.78)

So, rather than thinking of a screen as a just the TV in your living room or the smartphone in your pocket, she expands our thinking of screens as anything that can be projected onto, to create this ‘virtual window’, a term coined by theorist of modern media culture, Anne Friedberg, who has also acknowledged the ability of screens to allow us to exist in more than one place at a time and ‘distribute our presence', as she explains that, “screens work to produce an identity with ‘distributed presence’: windows provide a way for a computer to place you in several contexts at the same time...your identity on the computer is the sum of your distributed presence.” (Friedberg, A. 2006)

The kind of question this raises is, what it means to be physically present in a particular space and psychologically present in a whole new one? We can associate that feeling with the one you get when you look up from your phone and you feel like you’ve totally missed the conversation going on around you. Art critic Jonathan Crary says that “Attention is the feature of perception that enables subjects to focus on portions of their surroundings and delay or neglect the remainder.” (Crary, J. cited in Mondloch, K. 2010, p.21) The result of this is, that by trying to be both places at once, we inevitably end up being fully in neither. “Psychologically and physically invested simultaneously in the physical gallery space and in screen spaces - and being neither here nor there” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.79). In Robert Whitman's piece, ‘Shower’, he filmed somebody taking a shower, and projected this film onto a transparent plastic curtain and had an actual running shower head. (Fig. 1) Using elaborate systems of projections of light, shadows, slides, and films, Whitman created environments that weave together fantasy, reality, and fiction. Almost making the viewer feel like they are spying or witnessing a forbidden sight, Whitman forces us to question our role as viewers.

Fig. 1. Robert Whitman, ‘Shower’, (1931)

Whitman was among the first few artists to use new technologies as a tool for artistic creation and is heavily ingrained in the history of the use of screens in galleries and museums. “These intersections are the product of the technologies that at once makes us mobile, connected, and co-present.” (Verhoeff, N. 2016, p.4) Whitman’s work is an example of how screens can be expanded so far as to be “a connective interface to another (virtual) space” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.2)

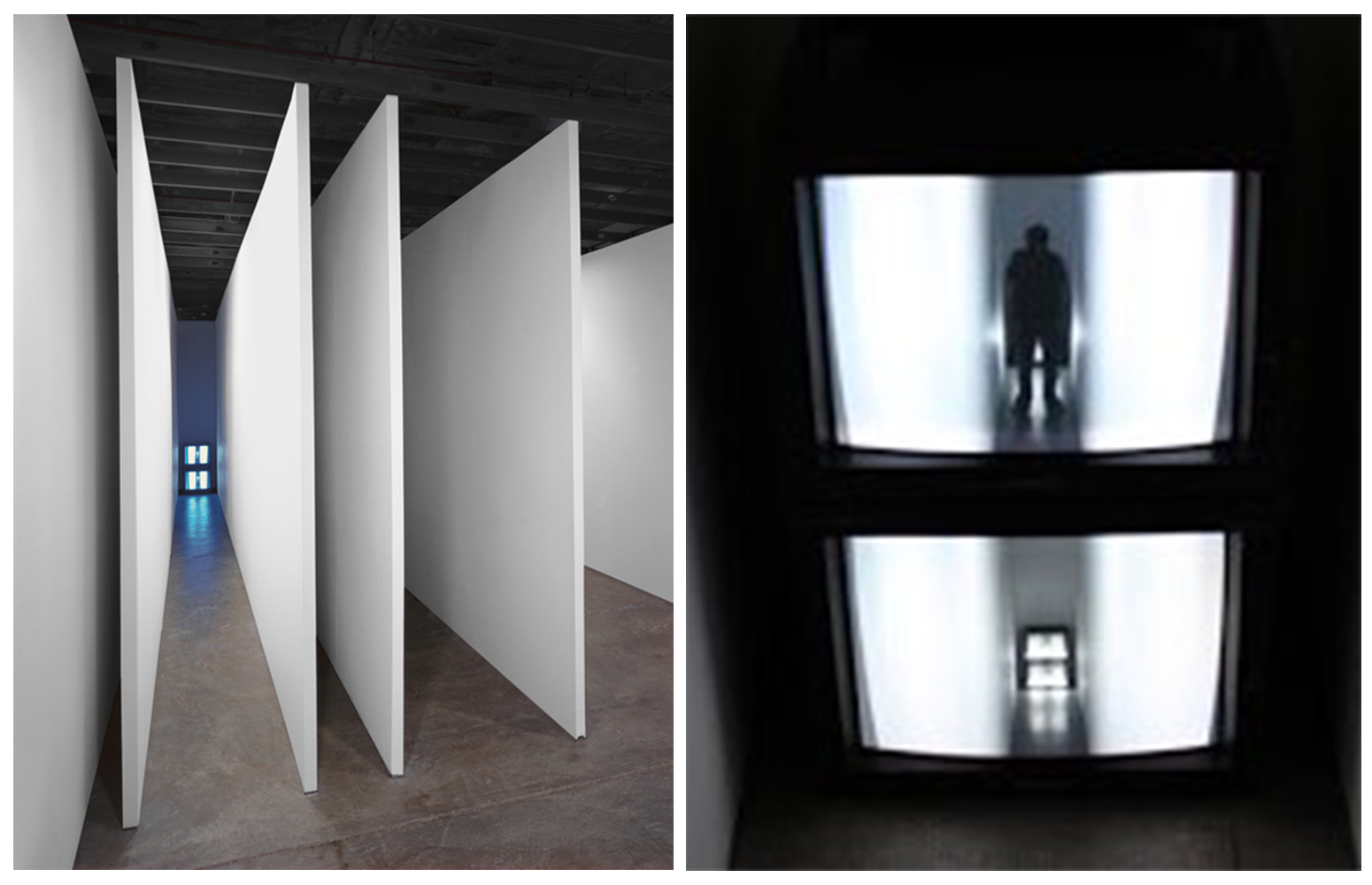

Bruce Nauman’s video corridor installations from the late 1960s and early 1970s, changed the way the viewer would interact in a space with screens and how they would become more aware of their own presence. “Indeed, the viewer’s involvement with the work is often taken to be the defining feature of the art form.” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.25) Nauman, in his piece ‘Live-Taped Video Corridor’ (1970) sets up a scene with surveillance cameras and two wallboard dividers mounted parallel to each other forming a passageway. (Fig. 2) There is a camera and two monitors stacked one on top of the other. As the viewer walks closer to the screen, they become aware of their body getting smaller in the real-time video. While on the second screen, the pre-recorded video remains unaltered, playing footage of the empty corridor, showing the space that the viewer is currently inhabiting remaining empty. (Fig.3)

Whitman was among the first few artists to use new technologies as a tool for artistic creation and is heavily ingrained in the history of the use of screens in galleries and museums. “These intersections are the product of the technologies that at once makes us mobile, connected, and co-present.” (Verhoeff, N. 2016, p.4) Whitman’s work is an example of how screens can be expanded so far as to be “a connective interface to another (virtual) space” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.2)

Bruce Nauman’s video corridor installations from the late 1960s and early 1970s, changed the way the viewer would interact in a space with screens and how they would become more aware of their own presence. “Indeed, the viewer’s involvement with the work is often taken to be the defining feature of the art form.” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.25) Nauman, in his piece ‘Live-Taped Video Corridor’ (1970) sets up a scene with surveillance cameras and two wallboard dividers mounted parallel to each other forming a passageway. (Fig. 2) There is a camera and two monitors stacked one on top of the other. As the viewer walks closer to the screen, they become aware of their body getting smaller in the real-time video. While on the second screen, the pre-recorded video remains unaltered, playing footage of the empty corridor, showing the space that the viewer is currently inhabiting remaining empty. (Fig.3)

Fig. 2 and 3: Bruce Nauman, ‘Live-Taped Video Corridor’, (1970).

There aren’t many other forms of art that respond to us, the viewer, quite like this does. “These participatory, experiential sculptures investigate the inter-penetration between the space ‘on’ the screen, the space between the viewer and the screen, and the space of the screen object itself.” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.26) The fascination of our surroundings reacting to us is a spectacle in itself, but works like this allow it’s viewers to see themselves in ways they never have before. With the focus of his work shifting to manipulate the movement and experience of the beholder, Nauman’s video corridor installations mark the pivotal moment of the possibility of transition from viewer to participant.

“These encounters are interactive: the subject, as both actant and user, is both produced at the interface, and the active co-producer of this subjectivity.” (Verhoeff, N. 2016. Pg.4)

Aborting all of our attention from our surroundings, screens have this ability to captivate their observer because of the ever-changing nature of the moving image. “If idolatry is the most dramatic form of image-power known to visual culture, it is a remarkably ambivalent and ambiguous kind of force.” (Mitchell, W. J. T. 2005, p.75) So how and where are we existing when we are standing in front of over 300 screens at one given time? This is the exact situation Nam June Paik (‘The Father of Video Art’) created in his most renowned work, ‘Electronic SuperHighway’ (1995) (Fig. 4) Using screens to translate how technology would influence society, Paik predicted an information overload and the potential for screens to be used as sculptural objects rather than simply just something to play a video/film on.

Fig. 4. Nam June Paik, ‘Electronic SuperHighway’ 1995.

“Moreover, whether mobile and portable, or architectural and fixed, screen-based technologies simultaneously multiply mobilities and perform situated presence.” (Verhoeff, N. 2016. Pg.3) Paik, in creating this work, allows us as viewers to think about screens as having the ability to create multiple modes of identity and exist in two (or more) separate time frames, creating ways in which we can use screens to illustrate the rapid improvement in technology.

In comparison to Whitman, Nauman and Paik, artists like Eija-Liisa Ahtilia continued to find new ways in which to use a screen, sequentially raising new questions as to how we, the viewers, interact with these screen-based installations and what it means to be present alongside these works. I will focus on Ahtila’s work ‘Potentiality For Love’ and how it explores screen-based interaction in order to evoke certain emotions from it’s viewer. This work raised many questions for me, in terms of how screens can allow us develop empathy far quicker than texts could. What is humanity’s potential for empathy not only towards itself but also towards other species? Can it be experienced through the use of screens? Can screens expand our potential for empathy?

Fig. 5: Eija-Liisa Ahtila, ‘Potentiality for Love’, 2018.

Carefully orchestrating how viewers will experience the work, Ahtila invites the viewer to slide their hands under a screen so that when they look down, they see a pair of hands belonging to an ape, rather than their own. (Fig. 5) This differs heavily from work’s like Nauman’s video corridors, as it is not time-based. It is not reacting to you, the viewer. The video is static, but what I find most interesting is how we allow ourselves to interact with the interface in order to become ‘co-producers’ of the work. “When both spatial contours and space-producing subjects are mobile, we can speak of a multiplied mobility—a mobility of, and with, the device.” (Verhoeff, N. 2016. Pg.5)

As Nauman’s corridor allows us to feel like we are changing the work, Ahtila’s piece creates a situation in which we allow the work to change us. “This visualizing makes the modern period radically different from the ancient and medieval world in which the world was understood as a book.” (Mirzoeff, N. 1998) Using screens as interfaces in this way can allow us to feel what it’s like to be something else, without changing the work from its original form. This, for me, shows that screens don’t have to be time-based to create empathy and therefore be transportive.

Artists like Whitman, Nauman, Ahtila and Paik used screens to create situations and raise questions that cannot be created through text alone. “The visual...offers a sensual immediacy that cannot be rivalled by print media: the very element that makes visual imagery of all kinds distinct from text.” (Mirzoeff, N. 1998, pg 9.) Using the powerful ability of screens to be their medium, as well as their platform and their format. “While the way in which viewer participation emerges as a form of submission has recently begun to be addressed in regard to installation in general.” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.26) How we interact with screen-based works is described by Mondloch as a kind of ‘submission’ to the work because of its ability to captivate the viewer.

“Questions about real and illusionary spaces achieve a new urgency” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.92) Through my reading of Mondloch’s ‘Screens’, I found myself connecting the dots to the world outside of art institutions, and how some of what she uncovers in investigating spectatorship towards screen-based media installation art can actually be applied to the impact of screens, such as our phones and laptops, seen in everyday life. “It takes wilful effort to avoid glancing at the moving images on the TV places above the bar in a saloon.” (Koch, C. 2004) I think it is really important to recognize the power of these screens and how drawn we are to them and even more importantly, why. “On the computer, we can be two (or more) places at once, in two (or more) time frames, in two (or more) modes of ‘identity’.” (Friedberg, A. cited in Mondloch, K. 2010, pg. 79) The rapid increase in use of screen-based technologies, smartphones in particular, has resulted in a huge lack of awareness of the power of these devices. Something that especially translates to screens outside of art institutions is their ability to allow us to exist in more than one place at a time and that this results in us being present in neither.

“The realization that spectatorship (the look, the gaze, the glance, the practices of observation, surveillance and visual pleasure) may be as deep a problem as various forms of reading (decipherment, decoding, interpretation, etc.) and that ‘visual experience’ or ‘visual literacy’ might not be fully explicable in the model of textuality.” (Mitchell, 1994, cited in Mirzoeff, N. p.5)

Screens are used universally today and our world pretty much revolves around them. I would go so far as to say that they are the greatest spectacle of today’s society. “Today, it is estimated that more than 5 billion people have mobile devices, and over half of these connections are smartphones.” (MacKay, J. 2019) One of the most interesting observations from Mondloch’s investigation into the spectatorship surrounding screens and the kind of ‘submission’ that comes along with them, is this state of being ‘lost in’ but in ‘control of’ time. This has become a huge problem in people not having the ability to be present in their physical space. “The time-shifting mobile spectator appears to be a close relative of the contemporary media subject; both are lost in yet determinedly struggling for the control of their experiences with screen-based technologies.” (Mondloch, K. 2010, pg. 58)

Oliver Grau identifies that there are “subjective effects to being in many places simultaneously” (Grau, O. cited in Mondloch, K. 2010. pg.79) Living in a society totally absorbed by screens, we can see how the use of these objects impacts our lives today, with social media constantly encouraging this incessant need to capture and share our lives with the rest of the world. Artists like Bjork have taken it upon themselves to ensure that their viewers are both present physically and psychologically in her show, by specifically requesting no use of mobile phones or cameras. What Bjork and many other artists and performers have done is to control their spectators experience, just like Nauman or Ahtila did but in a kind of upside down way. Artists like Whitman, Nauman, Paik and Ahtila, whose work is to be experienced in the gallery space, were enabling their viewer to exist physically in one place and psychologically be elsewhere. Whereas now we see artists like Bjork, whose art comes in a form that differs from installation art, trying to prevent that very thing.

Although the impacts of screen-based technologies are further acknowledged in media installation art, I think we have a lot to learn about how that translates to everyday experiences. There is still much to be uncovered regarding the impact of screens and screen-based technologies in art institutions as well as in everyday life. But as we can see, through the work of Whitman, Nauman, Ahtilia, Paik and through to Bjork, artists are forever progressing and changing the way we think about these often overlooked objects.

“These hybrid artworks - positioned as they are midway between the cinematic and the sculptural - deliberately engage the spatial parameters of the gallery, even as they reject it’s typical spatial and representational modes. They foreground the usually overlooked embodied interface between the viewing subject and the technological object.” (Mondloch, K. 2010, p.3)

If the use of screens, such as smartphones and cameras, is beginning to be monitored in public spaces, I think that it is pretty safe to say that screens have become a masterful part of today’s visual culture and that they are having a significant impact on how we interact with not only works in galleries or museums but how we interact with the world. We can learn from artists like Whitman, Nauman, Ahtila, and Paik, what it really means to be co-existing with these technologies and use that to further understand their capabilities.

If the use of screens, such as smartphones and cameras, is beginning to be monitored in public spaces, I think that it is pretty safe to say that screens have become a masterful part of today’s visual culture and that they are having a significant impact on how we interact with not only works in galleries or museums but how we interact with the world. We can learn from artists like Whitman, Nauman, Ahtila, and Paik, what it really means to be co-existing with these technologies and use that to further understand their capabilities.

Bibliography:

Acland, C. (2012). The Crack in the Electric Window. Cinema Journal. 51. Pg. 167-171.

Crary, J. ( Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modem Culture. (An October Book.) Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 1999.

Friedberg, A. (2006). The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press.

Jeong, S. (2013) Cinematic Interfaces: Film Theory After New Media.

Koch, C. ( 2004) The Quest for Consciousness: A Neurobiological Approach. Roberts & Company.

MacKay, J. (2019) Rescue Time Blog.

Accessed on: 22nd November, 2019

Accessed at: https://blog.rescuetime.com/screen-time-stats-2018/

Accessed on: 22nd November, 2019

Accessed at: https://blog.rescuetime.com/screen-time-stats-2018/

Mellencamp, P. (1995). The Old and the New: Nam June Paik. Art Journal, 54(4), 41-47.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas, (1998) “What is Visual Culture?” in Mirzoeff, Nicholas (ed), Visual Culture Reader, London: Routledge, pp. 3-13.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (2005). What do pictures want?: The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Mondloch, K. (2010). Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. University of Minnesota Press. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttsj4b

Mondloch, K. (2007). Be Here (and There) Now: The Spatial Dynamics of Screen-Reliant Installation Art. Art Journal. 66. 20-33.

Verhoeff, Nanna. (2016). Urban Interfaces: The Cartographies of Screen-Based Installations. Television & New Media. 18.

Fig 1. Robert Whitman, ‘Shower’, (1931).

Accessed on: https://www.artexperiencenyc.com/

Accessed at: November 1st, 2019

Fig 2. Bruce Nauman, ‘Live-Taped Video Corridor’, (1970).

Accessed at: https://www.schaulager.org/en/media/4/bruce-nauman

Accessed on: November 12th, 2019

Accessed on: November 12th, 2019

Fig 3. Bruce Nauman, ‘Live-Taped Video Corridor’, (1970).

Accessed at: http://alliecat8674.blogspot.com/2013/03/

Accessed on: November 12th, 2019

Accessed at: http://alliecat8674.blogspot.com/2013/03/

Accessed on: November 12th, 2019

Fig. 4. Nam June Paik, ‘Electronic Superhighway’. Photo: © Nam June Paik Estate

Accessed at: https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/photos/nam-june-paik-electronic-superhighway

Accessed on: 28th October, 2019

Accessed at: https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/photos/nam-june-paik-electronic-superhighway

Accessed on: 28th October, 2019

Fig. 5. Eija-Liisa Ahtila, ‘Potentiality for Love’, (2018).

Accessed at: https://www.biennaleofsydney.art/artists/eija-liisa-ahtila/

Accessed on: November 20th, 2019

Accessed at: https://www.biennaleofsydney.art/artists/eija-liisa-ahtila/

Accessed on: November 20th, 2019