‘The Development of the Cyborg in Art through Depiction, Exploration and Embodiment.’

Click here for downloadable PDF version.

Introduction

Artistic representation has historically been and continues to be a valuable medium for envisioning new bodily forms and for raising important questions regarding changes in what it means to be human in an era of rapid technological advancement (Hunt, 2015, p. 1).

The ethics of human advancement through the use of technology has long been a topic of discussion and has brought up many debates on its potential implications on the evolution of humanity. Through the investigation of cyborg art and performance, this research essay will aim to make evident the role of art in creating an incentive for discourse surrounding technological advancements and the subsequent redesigning of the human body. The artists explored in this paper have played a pivotal role in imagining ways in which we can develop alongside technology in order to prevent the extinction of the human race. By examining artistic representations of the three categories of the cyborg, from three different time periods, we can map its evolution from the early 20th century to the modern-day. These depictions envision new futures by predicting developments in technology and exploring ways in which they may challenge the fundamentals of what it means to be human. We will look at how artistic depictions of cyborgs challenge those that are presented to us in pop-culture, as well as the importance of maintaining a critical discourse surrounding new technologies. In order to do so, this paper will refer to Dunne and Raby’s Speculative Everything book, which explores the potential for critical and speculative design to function as a form of imagining new futures. Throughout, it will also make reference to the transhumanist movement1, whose thinking underpins much of what is being explored in these artistic representations, concerning the body and technology, and the potential merging of the two.

The first chapter will begin by defining the cyborg, acknowledging its roots in mythology, and examining how the effects of the war established the basis for the cyborgs earliest real-life applications. It will focus on the Dada movement in Berlin in the early 20th century and the work of their supposed founder and central figure Raoul Hausmann (Richter, 1985, p. 11), exploring how his early interpretations of human-machine hybrids played a significant role in promoting the re-examination of the human body. Building on this framework, chapter 2 will examine how Australian performance artist Stelarc, through his evocative body modifications and performance pieces of the late 20th century, exemplifies the research and experimentation phase of the cyborg. Stelarc’s work evokes an envisioning of new ways of thinking about how the human body could evolve beyond our current biological capabilities in order to prepare us for the biotechnology revolution2. Finally, chapter 3 will explore the work of performance artist and choreographer Moon Ribas, and how her work with the Cyborg Foundation is creating a community of people who are exploring their own ways of reimagining the human body and its potential to experience new abilities and senses in an effort to bring us closer to nature. This will hopefully allow us to gain an understanding of the development of the image of the cyborg from conceptualization to implementation.

As Heidegger suggests, in order to properly reflect upon the effects of technology, we must reflect upon something separate, such as the arts. He states that, “Because the essence of technology is nothing technological, essential reflection upon technology and decisive confrontation with it must happen in a realm that is, on the one hand, akin to the essence of technology and, on the other, fundamentally different from it. Such a realm is art (Heidegger, 1997, p. 14).” By reflecting upon the technologies used in these artists’ work, whether it be conceptually or physically, we can draw some interesting conclusions about how their work has influenced the development of the cyborg and society’s understanding of what it means to be human.

Chapter 1: Genesis of the Cyborg

When we hear the word cyborg, we may jump to thinking about the robots presented to us in pop-culture. Movies like Terminator, Blade Runner and A.I. Artificial Intelligence have blurred the public’s understanding of the distinction between cyborg and robot, making us far too familiar with the idea of the cyborg displayed as an apocalyptic scene where robots have developed beyond our control, or become intelligent and emotionally aware to the point where they seek dominance over their creator. These depictions are actually of highly developed machines that resemble human beings, as opposed to the ‘hybrid’ cyborg entities that will be explored in this paper. When examining this common narrative in science fiction movies, Goodall explains that they ultimately end in putting “biological humanity on the road to extinction” (Goodall, 2005, p. 1). These narratives have instilled widespread anxiety about robots taking our jobs, but as Fox illustrates, “debates about the future of society are flawed if they focus more upon robots than cyborgs” (Fox, 2018, p. 1). Fox imagines a society where it is the acceptance of humans becoming cyborgs that allows us not to be completely replaced by robots. As Hunt suggests,

“The cyborg is a sign which is all too often forced to signify one thing or another, most commonly the end of humanity or similar apocalyptic scenes. But the cyborg and alternate forms of hybrid beings in themselves do not signify such outcomes. This is why artistic visions and dreams of cyborg existences that escape tyrannical forces of signification provide an invaluable medium in which the sign of the cyborg can rebel (Hunt, 2015, p. 72).”

In order to understand the development of the cyborg through these artistic depictions, we must first understand what a cyborg actually is. Donna Haraway defines the cyborg in her Cyborg Manifesto, as “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” (Haraway, 1991, p. 149). The cyborg is similarly defined by Hunt, however, she states that “the term covers a wide spectrum of interconnections and fusions between the human body, the human psyche, and technological bodies” (Hunt, 2015. p. 5). In her paper I, Cyborg, Pearlman illustrates that there are three basic categories that cyborgs can be grouped into, there are “those that use mechanical elements” (eg. prosthetics), “those that use electronic elements”, (eg. prosthetics with the addition of electronics) and “those that use cybernetics as part of their body”, (eg. implants applied to the organism). These categories are “not fixed and can easily overlap” (Pearlmann, 2015, p. 84). In order to understand the vastness of cyborg forms, the artists we will be exploring each encapsulate one of these categories.

The discussion about the genesis of the cyborg must begin by acknowledging its roots in Greek and Roman mythological hybrid entities, known as chimeras (usually depicted as a fire-breathing female monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail). Hunt recognises that in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the chimeric figure experienced a technologic-mechanic recasting, which manifested in the form of the cyborg (Hunt, 2015, p. 5). This meant that these hybrid entities could now be thought of as fusions between human and machine, as opposed to the animal hybrids seen in the chimeras earliest depictions.

![]()

![]()

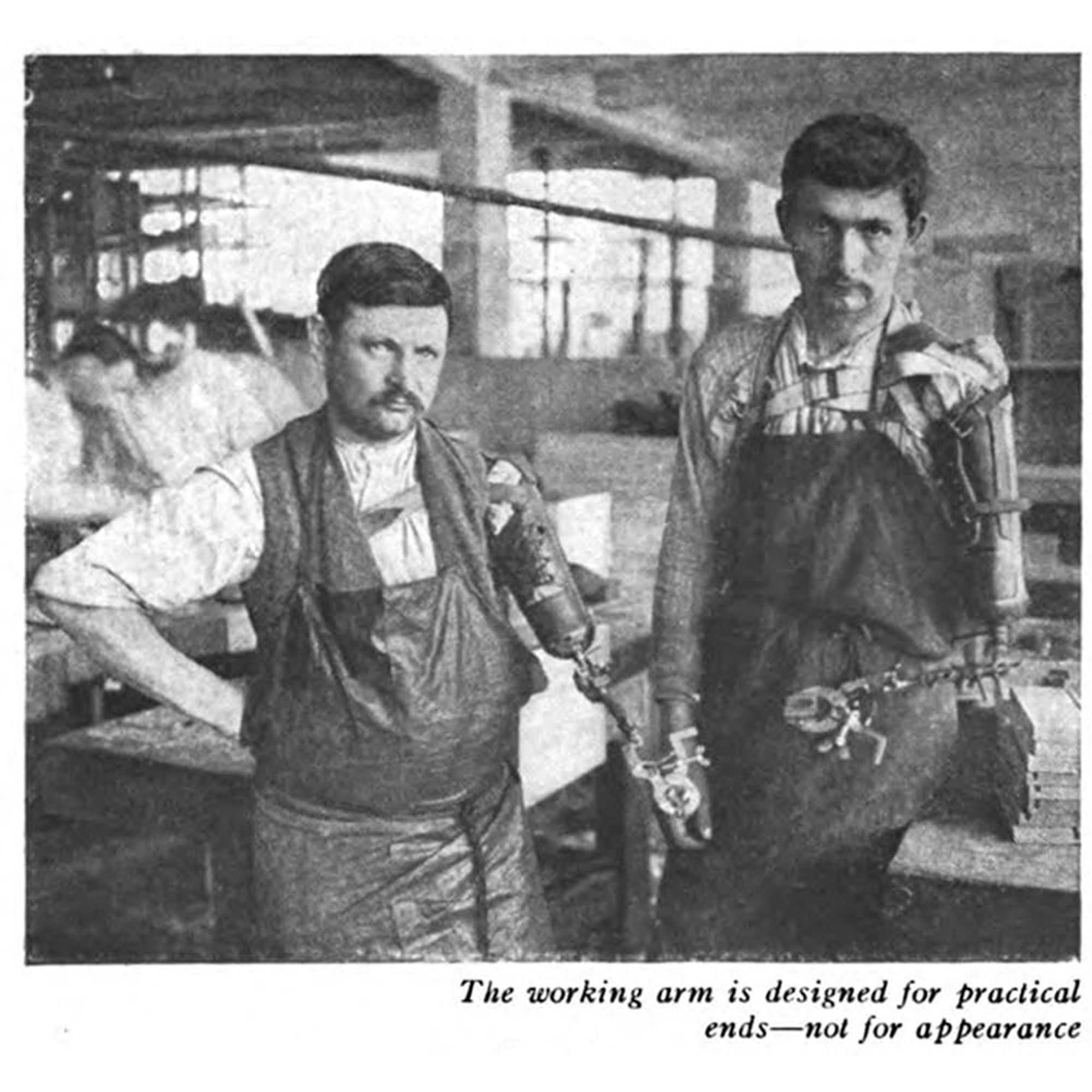

Fig. 1. Reconstructing the Crippled Soldier, McMurtrie, 1918.

The effects of the first world war revealed the frailty of the human body, and began a discourse surrounding the need for it to be improved upon. These new hybrid forms began to enter reality with an emergence of prosthetic limbs mimicking workforce tools in an effort to return wounded soldiers to the workforce (Fig. 1). During this time, due to the exponential development of technology, the idea of the cyborg began to develop a rich complexity. As Hunt illustrates, this merging of humans with machinery began to “call into question the definition of ‘human’ and its relation to the external world” (Hunt, 2015, p. 5).

The decision to create prosthetic limbs, that would give wounded soldiers the ability to be more productive than they were with their biological limbs, inspired many depictions of the cyborg in art, giving people the ability to look to the future and think about ways in which we can improve upon the human body. Both productivity and dissatisfaction with the human mind and body can be seen as the original driving forces in the development of the figure of the cyborg.

These developments heavily influenced the work of one particular art movement, known as Dadaism. The Dada movement produced work that was in protest against what they saw as a senseless war that had happened as a result of a society that made decisions influenced too much by emotion. Hunt explains that “after the destruction of World War I, the cyborg in art emerged as a figure that embodied hopes and utopian futures” (Hunt, 2015, p. 10). The Dadaists’ artwork communicated a desire for a society that acted with more mechanical, and less emotional reasoning. In Blumberg’s view, the Dadaists formed a critique of their society by “creating provocative works that questioned capitalism and conformity, which they believed to be the fundamental motivations for the war” (Blumberg, 2014, n.p.). As Biro illustrates in his book, The Dada Cyborg, the Dada movement and its strategies have been “acknowledged primarily not for their subject matter, but rather for the transformative effect they had on the viewer” (Biro, 2007, p. 26). By using the image of the cyborg as a means of imagining utopian futures and confronting their viewers with the potential effects of technological advancements, the Dadaist’s work evoked an introspective rethinking of what it means to be human. In Hunt’s view, these “hybrid and cyborg entities helped the Dada artists to grapple with the ambiguity and multivalence of their new reality – a world of technological advances” (Hunt, 2015, p. 9). Cyborg imagery became a sign of hope for the Dadaists, and a medium in which to imagine new modes of living post-war.

Dada artist Raoul Hausmann’s work acts as a catalyst in which to understand the genesis of the cyborg within art, exemplifying how new human futures were being explored in the early 20th century, and how art can be used to examine and critique technology and its effect on human evolution. Hausmann, among other Dada artists of his time, developed the process of ‘photomontage’. Hunt explains that while the Dadaists “literally combined images to create organic-technological hybrids”, the cyborg “more generally encompassed the idea of hybrid identity essential for understanding how new forms of existence and society were envisioned post-war” (Hunt, 2015, p. 10). Using imagery from mass-media sources, they evoked reflection upon technology within their society by imagining ways in which humans could potentially merge with machines. This construction of cyborg imagery through text and images would function as a form of constructing possible futures. Hunt explains that,

“Dadaism was, at its core, a manifestation of and reflection on new technological modes of being. As an artistic movement, Dadaism functioned as a critical carrier of cultural information, indicating a seismic shift in the way technology permeated and fundamentally altered the human conception of the self – in short, our ontology (Hunt, 2015, p. 7).”

![]()

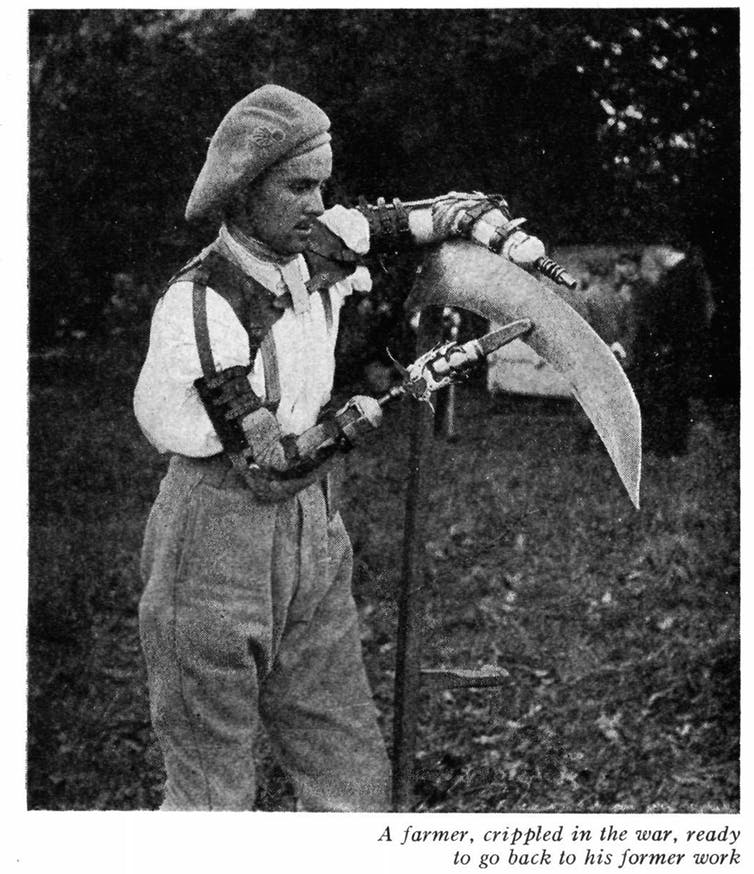

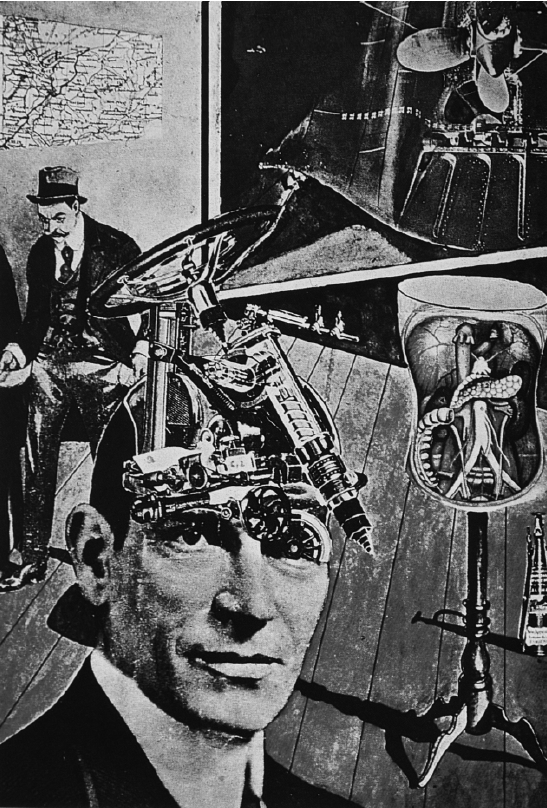

Fig. 2. Raoul Hausmann, Tatlin Lives at Home, 1920. Photomontage, 40.9 x 27.9 cm. Stockholm: Moderna Museet. Photo: 2007 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Hausmann’s famous photomontage Tatlin Lives At Home (Fig. 2) is an example of how these artists created cyborg entities to demonstrate this shift in our ontology. The relationship between technology, society and human identity is explored through the assembling and remixing of images of the human body and machines. By swapping out the brain for a strange mechanical mechanism, Hausmann illustrates the first category of a cyborg, one that uses mechanical parts, communicating the Dadaists desire for a peaceful society, one in which the mind only makes rational and reasoned decisions. As Biro explains, Tatlin Lives At Home presents “allegorical representations” of the cyborg, to “disrupt reality in an effort to imagine new modes of existence” (Biro, 2007, p. 44). Photomontage became a medium in which Hausmann could merge images from many different sources in order to “project his utopian hopes and fantasies” (Biro, 2009, p. 1). Tatlin Lives At Home utilises the cut and paste aspect of photomontage to “shatter reality into a multiplicity of disconnected fragments”, allowing the re-assembling of these fragments to create “new forms of hybrid identity better able to exist in the modern world” (Biro, 2007, p. 45). This work allowed Hausmann’s viewers to see these depictions as a way of literally breaking down what it means to be human, in order to rebuild our idea of humanity, only now, inclusive of elements of technology and mechanical parts. Hausmann saw this to be the solution to preventing catastrophic events such as the war.

By Dada artists such as Hausmann envisioning cyborg entities, they “hoped to influence this figure’s development, encouraging the forms that they found beneficial and attacking the other types that they believed were highly destructive” (Biro, 2009, p. 64). By using technology as a conceptual theme in his work, and envisioning ways in which we could benefit from the addition of machinery to our bodies, Hausmann begins a discourse surrounding the ways in which we could harness the power of technology to control our evolution. Biro explains that Hausmann’s cyborgs “implied that technological augmentation carried both extreme benefits and extreme risks” (Biro, 2007, p. 31). He provokes us to imagine our own futures involving technology, and think about what elements of this way of living makes us uncomfortable, or that we’d like to leave behind. Hausmann’s photomontages create “testimonials to what could be”, as well as offering “alternatives that highlight weaknesses within existing normality” (Dunne and Raby, 2013, p. 34-35). In this case, Hausmann’s work highlighted the frailty of the human body, as well as our minds. Tatlin Lives at Home shows us that by breaking down our idea of what it means to be human, it is possible to rebuild ourselves into beings who are capable of coexisting with technology.

According to Biro, the Dada artists were oftentimes making work about subjects that didn’t even exist yet (Biro, 2007, p. 27). Hunt informs us that the term ‘cyborg’ wasn’t actually part of the Dada artists vocabulary at this point, although it “aptly captures Dadaists reconceptualization of embodiment and the interconnections they saw rapidly emerging between humans and technology” (Hunt, 2015, p. 9). Unbeknownst to Hausmann, these ideas would become vital in the ever-changing climate of rapid technological advancements, and would actually go on to form the basis of what is considered transhumanist ideology today. As defined by Mark O’ Connell in his book To Be A Machine, the transhumanism worldview is a “conception of our minds and bodies as obsolete technologies, outmoded formats in need of complete overhaul” (O’ Connell, 2017, p. 11). Hausmann and his contemporaries explored and experimented with the redesigning of the human body and the ways in which we can actually enact this ‘overhaul’. By taking on this role, the Dadaists can be characterised as “artistic pioneers of an investigation into ‘the self’ and the parallel reconceptualization of human identity in the early 20th century” (Hunt, 2015, p. 8).

Through the promotion of a re-examination of human identity, Dada artists in Berlin during the early 20th century used cyborg imagery to provide “an invaluable strategy for reading the world and confronting its emerging changes” (Hunt, 2015, p. 15). It was precisely this dedication by artists such as Hausmann, to create work that is an expression of their society’s most vital concerns, that “triggered an investigation of the discordant concepts of self and society” (Hunt, 2015, pg 11). Hausmann’s visions of human-machine hybrids can be seen as some of the first portrayals of how humans may benefit from the addition of machinery to the body. This aptly marks the genesis of cyborg entities in art and paves the way for many more artistic depictions of human advancement through technology and the imagining of hybrid forms and new realities.

Chapter 2: Demonstrating The Cyborg Through Performance

In his paper, Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution, Fukuyama argues that if developments in cybernetics3 and biotechnologies4 are left unchecked, there could be catastrophic consequences for humanity. This highlights the essential role of criticality when exploring such developments. As Fukuyama illustrates, there are two solutions to this problem, the first being to “forbid the use of biotechnology to enhance human characteristics and decline to compete in this dimension”, which is quickly discarded as an option, due to the attractiveness of such enhancements and the complications that would arise in preventing them. Fukuyama concludes that “a second possibility opens up, which is to use that same technology to rise up from the bottom” (Fukuyama, 2002, p. 11). This chapter will examine the work of Australian performance artist Stelarc, and will use his practice as a catalyst for understanding the experimentation phase in the development of the cyborg. Stelarc’s practice illustrates how exploring advancements in technology through performance can help us envision new modes of being, so that technology “remains man’s servant rather than his master” (Fukuyama, 2002, p. 1).

If the Dadaists were at the forefront of imagining these utopian hopes and futures, then Stelarc could be said to be at the forefront of actually experimenting with ideas surrounding the human body’s ability to merge with machines. Advances in technology spanning 60 years, (from the Dadaists in the 1920s to Stelarc in the 1980s), would make it possible for the imagining of cyborg entities to enter reality. Hausmann conceptualised ideas that Stelarc could now manifest. By utilising emerging technology, Stelarc’s artistic practice explores its ability to control the evolution of the human body and how these technologies may prevent our obsolescence. Kroker and Kroker believe that “in a dramatic instance of art as a precession of reality, we are living in a world whose main scientific and technological features have been accurately forecast and artistically performed by Stelarc” (Kroker & Kroker, 2005, p. 63). This chapter will examine how Stelarc’s practice brought Hausmann’s concepts into real-life experiments and how they continue to map the development of the cyborg by adding to the discussion of ways in which we can extrapolate and imagine new futures for humanity through the use of technology.

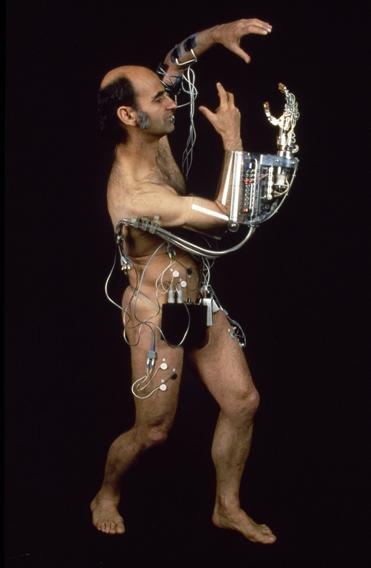

Stelarc’s Third Hand performance (Fig. 3), completed in 1980, illustrates one of the many ways in which he has developed upon the Dadaists’ reimagining of the human body. This performance explores the augmentation of his body by extending its capabilities, and is a perfect example for looking at the second category of a cyborg, one that uses electronic elements. This prosthetic resembles a third hand and is capable of picking up electric signals from different muscles around the body and sending them to a switching system device on the mechanical third hand in order to give it commands. By exploring the passing over of agency of one’s body to another source, this performance raises important questions around who will have the agency to control our bodies, if these technologically advanced prosthetics were to become our reality.

![]()

Fig. 3. Third Hand, Tokyo, Nagoya, Yokohama, 1980. Photo by Simon Hunter.

Stelarc explains that Third Hand has become a “body of work that explores the intimate interface of technology and prosthetic augmentation - not as a replacement but rather as an addition to the body. A prosthesis not as a sign of lack, but rather a symptom of excess” (Stelarc, 2022, n.p.). Similar to the wounded soldier’s prosthetics, Stelarc’s Third Hand is not an attempt to substitute something that is missing, but to give the body new abilities that were previously unattainable. In doing so, Stelarc “probes our anxiety over maintaining a “pure” body and questions whether such a concept still even exists or carries meaning” (Hunt, 2015, p. 71). The addition of prosthetics and technology to the body calls into question what it means to be human, and questions how much more or less human we may become when we merge with machines.

Stelarc believes that “it is only when the body becomes aware of its present predicament that it can map its post-evolutionary strategies” (Stelarc, 1991, p. 591). This claim by Stelarc signifies that we must accept the dissatisfaction with the human body in order to reimagine new modes of being that will prepare us for the future. Third Hand can be seen as one of these post-evolutionary strategies that enable us to move away from this “fear of obsolescence”, of what Goodall writes as “being the losing species in the competition for progress through adaptive advantage” (Goodall, 2005, p. 2). Stelarc’s work allows the cyborg to ‘rebel’ against the prototypical narrative presented to us within pop-culture, demonstrating the incredible ways in which technological developments can prepare us for the future, as well as highlighting the complications that may come along with them. Hunt explains that Stelarc “employs this technological power in order to explore how we might quell our anxieties of hybrid beings and nonhuman others, instead envisioning pleasure in their existence” (Hunt, 2015, p. 71). Through his artistic practice, and performances such as Third Hand, Stelarc depicts ways in which we can use technology to augment and improve upon the human body, ultimately signifying a changing narrative from robots taking over the world to one where we could live harmoniously alongside technology.

Garoian & Gaudelius, in their paper Cyborg Pedagogy, speak of performance art as having the ability to provide artists with “a public arena within which to re-claim and re-present their bodies” (Garoian & Gaudelius, 2001, p. 335). This indicates that art can become a space in which to experiment, a space in which there is room for trial and error, failures and glitches. As Legacy Russel states, “via the cyborgian turn, the artist intentionally embodies error” (Russel, 2020, p. 45). It is this free-thinking ‘public arena’ and the confidence to embody errors that allows Stelarc to come to conclusions otherwise perhaps intangible, had a rigid set of instructions and desired outcomes been put in place, as they would in scientific experiments. Stelarc speaks of this distinction between scientific and artistic research in a talk given at Curtin University when he states that;

“As artists, we’re not interested necessarily in doing methodical scientific research for immediate utilitarian use but rather generating contestable futures, contestable possibilities that might be examined, possibly appropriated, often discarded, but that contribute to that discussion and that interrogation of what it means to be human (Stelarc, 2014).”

Further influencing modern-day transhumanist thought, Stelarc is preoccupied with finding ways in which we can prevent the obsolescence of the human body (Goodall, 2005, p. 1). Much of what drives Stelarc’s practice is the view of the body as being frail and having a vulnerability attached to the idea of being human, as he believes that “the body is neither a very efficient nor a very durable structure, it malfunctions often and fatigues quickly” (Stelarc, 1991, p. 591). Stelarc’s performances can be seen as a series of explorations into how we can improve upon the human body by envisioning it to be more durable and more able to perform for long periods of time, ultimately for it to be more capable than it currently is. It’s evident that this thinking has influenced transhumanist ideology as O’Connell writes that “the underlying premise of transhumanism, after all, was that we all needed fixing, that we were all, by virtue of having human bodies in the first place, disabled” (O, Connell, 2017, p. 215). By thinking about the body as being a kind of structure or architecture, Stelarc explores ways that the addition of technology to the body can allow it to extend its original capabilities, as he sees the body “not as a subject but as an object - not as an object of desire but as an object for designing” (Stelarc, 1991, p. 591). This allows us to recognise that productivity and dissatisfaction with the body’s abilities continue to be the incentive for the development of the cyborg into the late 20th century. O’Connell writes with regard to the transhumanists desires, that these explorations are in an effort to “become better versions of the devices that we were: more efficient, more powerful, more useful” (O, Connell, 2017, p. 5). Stelarc’s explorations surrounding such developments are extremely important in furthering society’s understanding and acceptance of them. By confronting us with the capabilities of these advancements, and the potential realities that they may make possible, Stelarc’s work allows us to question what the essence of humanity is and how much we want technology to change the course of our natural evolution.

With regards to his work with the Alternate Anatomies Lab (AAL), Stelarc speaks about how technology fundamentally determines what it means to be human and how it “is determined historically, culturally and by the technology that is available” (Stelarc, 2014). O’Connell illustrates how this thinking is core to transhumanist ideology as they believe that “our future is predicated in large part on what we might accomplish through our machines” (O’ Connell, 2017, p. 6). This point is reiterated by Richter when he writes that “art in its execution and direction is dependent on the time in which it lives” (Richter, H. 1985. p. 104). This idea intensifies the importance of experimenting with these technologies in order to understand their capabilities, and ultimately as a form of furthering our understanding of ourselves.

Where Hausmann’s photomontages formed the blueprints for ways in which the human body could merge with machines, Stelarc’s performances began to lay down the foundation for ways in which the human body might extend its biological capabilities, giving us the opportunity to explore the elements of his work that make the viewer feel uncomfortable or untrustworthy of the technologies he is using. As stated by Hunt, the “use of cyborg and hybrid identity plays a crucial role in renegotiating the space of the human body and forming a new subjectivity” (Hunt, 2015, p. 15). Stelarc’s work allows us to see ways in which we can use these new technologies in order to prepare us for the future, and does precisely what Dunne and Raby say is essential to any critical design, as it can be seen as an “expression or manifestation of our sceptical fascination with technology, a way of unpicking the different hopes, fears, promises, delusions, and nightmares of technological development and change” (Dunne and Raby, 2013, p. 35). Stelarc’s practice explores and experiments with the redesigning of the human body and proposes ways in which we can prevent our bodies from becoming obsolete. These investigations into the capabilities of a technologically advanced human body open up avenues for us to imagine what we want our future to look like. By exploring ways in which the body can be redesigned, Stelarc believes that “the artist can become an evolutionary guide, extrapolating new trajectories; a genetic sculptor, restructuring and hypersensitizing the human body” (Stelarc cited by Hunt, 2015, p. 71). Using physical technology in his performances, Stelarc gives us the ability to form our own speculations of the future of the human body and how we may merge with such technology, fundamentally changing the perception of what it means to be human.

Chapter 3: Evolving Perception Through Cyborg Embodiment

This final chapter will look at the implementation phase in the development of the cyborg by examining the work of Moon Ribas, a Spanish artist, dancer and choreographer. Demonstrating the third category of a cyborg, her practice focuses not on the bionic body, but on the extension of our senses through cybernetics. Ribas co-founded the Cyborg Foundation in 2010 with fellow cyborg Neil Harbisson, which essentially “helps people become cyborgs; by extending their senses by applying cybernetics to the organism”, they also work to “defend cyborg rights and promote the use of cybernetics in the arts” (Cyborg Foundation, 2020, n.p.). They were inspired to do this after they discovered that there were “no special clinics where physicians and computer scientists could collaborate on devices and develop new ideas together” (Pearlman, 2015, p. 89). Over the last 12 years, Ribas and Harbisson have inspired and helped people to find a way to perceive new senses or repair lost ones, influencing the acceptance of the idea of becoming a cyborg. By examining the work of the Cyborg Foundation and taking an in-depth look at one of Ribas cyborg performances, this chapter will explore how Ribas is developing the public’s understanding of the biotechnology revolution by giving them the tools and knowledge to imagine their own post-evolutionary modes of living. Ribas plays a crucial role in mapping the current developments in the evolution of the cyborg.

![]()

Fig. 4. Moon Ribas, Waiting For Earthquakes at Hyphen Hub, 2014. Photo by Ellen Pearlman.

The work by Ribas that this paper will focus on is her performance Waiting For Earthquakes (Fig. 4), which is made possible by the fact that she has implanted seismic sensors in her arms, that are connected to a global seismograph, and can indicate to her when there is an earthquake happening anywhere in the world. If her sensors pick up seismic activity, they can also inform her of the location of the earthquake. Pearlman explains that “during the performance, the exact place the quake is taking place is shown, and its intensity projects on a screen behind her, along with the current location, date, and time” (Pearlman, 2015, p. 88). Similar to some of Stelarc’s performances, Ribas explores the passing over of agency of her body to cybernetics, and artistically performs the outcomes, as she allows the vibrations to influence the movement of her body. This allows the viewer to consider “the possibility of the human body acting as a conduit for data collected from external, natural forces” (Tokareva, 2016, n.p.). What this performance explores is the use of technology as an extension of human perception and the ways in which we can use technology to bring us closer to nature, rather than the role that many modern technologies play in alienating us from it and each other. Rather than trying to change the environment around us, Ribas performances explore ways in which our bodies can be made more capable of living in our ever-changing climate. Ribas and many other members of the Cyborg Foundation have developed interesting ways in which we can reconnect with nature in this way, some having implanted technology that acts as a compass, allowing them the ability to tell their direction in the world, eliminating their reliance on navigation technology such as Google Maps.

Developments in nanotechnology5 have meant that technologies are getting smaller and smaller, so they no longer need to be outside of us, but will become part of the make-up of who we are. Garoian & Gaudelius argue that “performance art enables us to use the cyborg metaphor to create personal narratives of identity as both a strategy of resistance and as a means through which to construct new ideas, images, and myths about ourselves living in a technological world (Garoian, & Gaudelius, 2001, p. 337). It seems that much of the inspiration for these new senses comes from the abilities of animals, with other cyborgs having abilities such as night vision, echolocation, infrared and ultraviolet vision, as well as electric, seismic and magnetic senses. This gives these people the ability to perceive the invisible, and thus begins to change the ways in which they look at and utilise the world around them. The Cyborg Foundation aims to challenge the public’s perception that technology can only alienate us from nature, and to show people that it can be used to gain a deeper understanding of nature and feel more connected to our planet.

The effects of WW1 gave rise to the first wave of discussion into the ethics of human advancement, where society became extremely concerned about its effects on humanity and the human body. It is now apparent that we are in the second wave of such discussions deeming what is ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’, ‘human’ and ‘non-human’, and there seems to be a wider acceptance this time around. But as pointed out by Garoian and Gaudelius, there is still a disparity between why some technologies are commonly accepted and others are not, as they examine how normalized implants are when being used on sick bodies as opposed to the great sense of disgust when it comes to implants in healthy bodies.

“In the healthy body such prosthetics become the marker of abjection, the non-human. This difference in the value that we assign to such devices is of critical importance for it renders the cyborg body as harmless when its purpose is to restore the semblance of lost humanity, but as monstrous when the body is healthy (Garoian & Gaudelius, 2001, p. 336).”

Ribas is challenging this thinking by extending her senses and demonstrating what can be achieved with these new abilities. This is imperative in changing the narrative of prosthetics or the addition of technology to the body as being the sign of excess that Stelarc spoke about, as opposed to it being a sign of lack. As Garoian, & Gaudelius speculate, “the performance of the self as cyborg represents an overt political act of resistance in the digital age” (Garoian, & Gaudelius, 2001, p. 337). Ribas’ work can be seen as a form of resistance against the idea that technology makes us less human and proves that you don’t need to be sick or have an illness in order to merge with machines.

Pearlman states that “in 100 years from now it will be quite normal to be a cyborg” (Pearlman, 2015, p. 89), but according to Haraway, we are already “all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs” (Haraway, 1991, p. 150). This allows us to question what is ‘pure’ in a society where we no longer rely on our own memory, sense of direction, or trust a device to tell us when to hydrate? At what point can we agree that we’re already well on our way to becoming cyborgs? Hayles speculates that if we consider the use of implanted technologies such as pacemakers, hearing aids and prosthetic limbs, in the technical sense, approximately 10% of the U.S. population are already cyborgs (Hayles, 1999, p.115). Garoian & Gaudelius elaborate on how people perceive implanted bodies when they write that “it becomes evident that such manifestations of embodied technology, such joining of machine and human, are not seen as frightening but as beneficial (Garoian & Gaudelius, 2001, p. 335). Ribas’ Waiting For Earthquakes performance shows us one of the many ways in which this merging can be beneficial.

Dunne and Raby point out the impact that the public’s decisions have on how our future will manifest, by explaining that, “manufacturers are never sure which reality we will embrace or reject, they simply offer them up and do their best through advertising to influence our choices” (Dunne and Raby, 2013, p. 37). Similarly, tech companies can’t be sure which technological reality we will embrace. Ribas acts as a mediator between the public and our potential new modes of being, and in doing so, creates the incentive for discourse that is essential for any good critical design, as it is “the gap between reality as we know it and the different idea of reality referred to in the critical design proposal that creates the space for discussion” (Dunne and Raby, 2013, p. 35). By Ribas exploring cybernetics before they become widely accepted into mainstream culture, she confronts her audience with the possibilities that they can create for us, as well as the many potential futures that accepting such technological advancements could lead to.

These cyborg performances allow us to see unconventional ways in which a cyborg body could help us map our post-evolutionary strategies. Broadhurst explains that “the body serves as a language to talk about the body, it writes itself literally in performance rather than supporting something that is spoken” (Broadhurst, 2017, p. 14). Ribas’ use of the body in her artistic practice allows her to move past mere hypothesising, and onto embodying these technologies. Ribas cyborg performances enable us to “expose, examine, and critique the ways in which the body is complicated and bound up in our understandings of art, technology and identity” (Garoian, & Gaudelius, 2001, p. 333). In this way, the cyborg is bound up in our ability to understand ourselves, our bodies, and our futures. Ribas’ performances, as well as her work with the Cyborg Foundation, adjust and extend our awareness of the world. By encouraging her viewers and collaborators to take agency over the redesigning of their bodies and enabling them to “improvise their own extensions” (Pearlman, 2015, p. 89), Ribas has created a community that functions to share knowledge and resources, while also tackling negative connotations of being a cyborg. Her work has played a crucial role in furthering the development of the cyborg and demonstrates the fact that we have the ability to have our say in how much technology challenges what it means to be human.

Conclusion

This paper has examined how these artists have shown us ways in which the cyborg can allow us to “reject traditional ontological distinctions between the natural and the artificial and thus invites us to consider a subjectivity that extends into the nonhuman world” (Cheney-Lippold, 2017, p. 162). They have done so by using their artistic practices to question, experiment, research, and in some cases, even offer themselves up as willing participants to explorations in technological advancements, in an effort to prevent the extinction of humanity. In Virilio’s view, “a real artist never sleeps in front of new technologies but deforms them and transforms them” (Virilio cited in Zurbrugg, 1999, p. 49). It is precisely this deforming and transforming of cyborg entities that reveals their capabilities, and that gives the public the knowledge and tools with which to accept or reject these proposed modes of humans merging with machines. These artists are using their practice as a space to experiment, a free-thinking ‘public arena’ in which to highlight, question and critique the development of the cyborg. In so doing, they allow us, their spectators, an opportunity to be confronted with the reality of some of the potential ‘utopian’ futures that could be in store for the human race. These artists question our understanding of what it means to be human by probing new modes of becoming-with and experiencing technology. Through their imagined utopian futures, they enable us to move away from the fear of obsolescence, by demonstrating the incredible ways in which technological developments can prepare us for the future, as well as highlighting the complications that would come along with them. Their work can be seen as a form of preparing and priming our minds as well as our bodies for the predicted shift in our ontology.

This paper began by examining Hausmann’s work from the early 20th century depicting the conceptualization phase in the development of the cyborg, with his photomontages communicating the Dadaists desire for humans to think more mechanically. Moving through to the late 20th century, advancements in technology are being explored by Stelarc, whose performances began to utilize electronics and technology in order to explore ways in which humans could merge with machines, furthering the development of cyborg entities and transforming them from concepts to realities. Finally, we arrived at the present day, where we examined the work of Moon Ribas and the Cyborg Foundation and how they are influencing society’s acceptance of cyborg entities and more importantly, finding ways in which these new modes of living may solve one of the most concerning issues of our time, the climate crisis. In the span of the last 150 years, we see the development of the cyborg go from re-assembled imagery to being actualised through experimentation, from brainstorming to bodystorming. As Broadhurst and Price point out, “it can be posited that the exponential growth of digital technology has affected the way we think, reflect on ourselves, interact with the world, and create” (Broadhurst & Price, 2017, p. 2). Whether it’s through photomontage, performance or even working with prosthetic limbs, it is evident that art can be a useful tool for mapping the development of the cyborg, highlighting how developments in technology may affect both our mind and body, as well as our culture and society. Hausmann, Stelarc and Ribas all form a critical discourse surrounding the technologies explored in their practices. In doing so, they are providing us with alternative modes of being and creating an incentive for discourse surrounding both positive and negative effects of the biotechnology revolution and how cyborg depictions are challenging the fundamentals of what it means to be human.

Glossary

Bibliography

Apter, M. J. (1969) ‘Cybernetics and Art’, Leonardo, 2(3), pp. 257–265.

Blumberg, N. (2014) ‘Raoul Hausmann’, Encyclopedia Britannica.

Available at: Raoul Hausmann | Austrian artist | Britannica (Accessed: 18 November 2021).

Biro, M. (2007) ‘Raoul Hausmann's Revolutionary Media: Dada Performance, Photomontage and the Cyborg’, Art History, 30(1), pp. 26–56.

Biro, M. (2009) The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin. USA: University of Minnesota Press.

Broadhurst, (2017) Digital Bodies. UK: Palgrave Macmillan UK

Cheney-Lippold, J. (2017) We Are Data: Algorithms and the Making of Our Digital Selves. Washington, New York: New York University Press.

Cyborg Foundation (2020) Cyborg Foundation Website.

Available at: Home | Cyborg Foundation (Accessed: 2 November 2021).

Dunne, A. and Raby, F. (2013) Speculative Everything. Cambridge Massachusetts, London, England: The MIT Press.

Fox, S. (2018) ‘Cyborgs, Robots and Society: Implications for the Future of Society from Human Enhancement with In-The-Body Technologies.’ Technologies, 6(2):50.

Garoian, C. R., and Gaudelius, Y. M. (2001) ‘Cyborg Pedagogy: Performing Resistance in the Digital Age’. Studies in Art Education, 42(4), 333–347.

Goodall, J. (2015) Stelarc: The Monograph. London: The MIT Press.

Haraway, D (1991) Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. London: Free Association Books.

Hayles, K. (1999) How We Became Posthuman. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Kavanagh, C. (2019) ‘Biotechnology’, In New Tech, New Threats, and New Governance Challenges: An Opportunity to Craft Smarter Responses?, pp. 23–30.

Kroker, A & Kroker, M, (2005) ‘We Are All Stelarcs Now’ in Goodall, J. Stelarc: The Monograph. London: The MIT Press.

O Connell, M. (2017) To Be A Machine. London: Granta Publications.

Pearlman, E. (2015) ‘I, Cyborg’, PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, 37(2), 84–90.

Richter, H. (1985) Dada, Art and Anti-Art. New York, USA: Thames and Hudson.

Russell, L. (2020) Glitch Manifesto. London: Verso Publications.

Stelarc (1991) ‘Prosthetics, Robotics and Remote Existence: Postevolutionary Strategies’, Leonardo, 24(5), 591–595.

Stelarc (2014) ‘Zombies, Cyborgs & Chimeras: A Talk by Performance Artist, Prof Stelarc’, Curtin University [Artist Talk]. 6 August 2014.

Available at: https://youtu.be/TqtiM1hK6lU (Accessed: 1 November 2021).

Stelarc (2022) Stelarc Website.

Available at: STELARC | THIRD HAND (Accessed: 10 December 2021)

Tokareva, A. (2016) “Waiting for Earthquakes” — Moon Ribas

Available at: “Waiting for Earthquakes” — Moon Ribas – (Accessed on: 29 December 2021)

Zurbrugg, N. (1999) ‘Virilio, Stelarc and Terminal Technoculture’, Theory, Culture & Society, 16(5–6), pp. 177–199.

Click here for downloadable PDF version.

Introduction

Artistic representation has historically been and continues to be a valuable medium for envisioning new bodily forms and for raising important questions regarding changes in what it means to be human in an era of rapid technological advancement (Hunt, 2015, p. 1).

The ethics of human advancement through the use of technology has long been a topic of discussion and has brought up many debates on its potential implications on the evolution of humanity. Through the investigation of cyborg art and performance, this research essay will aim to make evident the role of art in creating an incentive for discourse surrounding technological advancements and the subsequent redesigning of the human body. The artists explored in this paper have played a pivotal role in imagining ways in which we can develop alongside technology in order to prevent the extinction of the human race. By examining artistic representations of the three categories of the cyborg, from three different time periods, we can map its evolution from the early 20th century to the modern-day. These depictions envision new futures by predicting developments in technology and exploring ways in which they may challenge the fundamentals of what it means to be human. We will look at how artistic depictions of cyborgs challenge those that are presented to us in pop-culture, as well as the importance of maintaining a critical discourse surrounding new technologies. In order to do so, this paper will refer to Dunne and Raby’s Speculative Everything book, which explores the potential for critical and speculative design to function as a form of imagining new futures. Throughout, it will also make reference to the transhumanist movement1, whose thinking underpins much of what is being explored in these artistic representations, concerning the body and technology, and the potential merging of the two.

The first chapter will begin by defining the cyborg, acknowledging its roots in mythology, and examining how the effects of the war established the basis for the cyborgs earliest real-life applications. It will focus on the Dada movement in Berlin in the early 20th century and the work of their supposed founder and central figure Raoul Hausmann (Richter, 1985, p. 11), exploring how his early interpretations of human-machine hybrids played a significant role in promoting the re-examination of the human body. Building on this framework, chapter 2 will examine how Australian performance artist Stelarc, through his evocative body modifications and performance pieces of the late 20th century, exemplifies the research and experimentation phase of the cyborg. Stelarc’s work evokes an envisioning of new ways of thinking about how the human body could evolve beyond our current biological capabilities in order to prepare us for the biotechnology revolution2. Finally, chapter 3 will explore the work of performance artist and choreographer Moon Ribas, and how her work with the Cyborg Foundation is creating a community of people who are exploring their own ways of reimagining the human body and its potential to experience new abilities and senses in an effort to bring us closer to nature. This will hopefully allow us to gain an understanding of the development of the image of the cyborg from conceptualization to implementation.

As Heidegger suggests, in order to properly reflect upon the effects of technology, we must reflect upon something separate, such as the arts. He states that, “Because the essence of technology is nothing technological, essential reflection upon technology and decisive confrontation with it must happen in a realm that is, on the one hand, akin to the essence of technology and, on the other, fundamentally different from it. Such a realm is art (Heidegger, 1997, p. 14).” By reflecting upon the technologies used in these artists’ work, whether it be conceptually or physically, we can draw some interesting conclusions about how their work has influenced the development of the cyborg and society’s understanding of what it means to be human.

Chapter 1: Genesis of the Cyborg

When we hear the word cyborg, we may jump to thinking about the robots presented to us in pop-culture. Movies like Terminator, Blade Runner and A.I. Artificial Intelligence have blurred the public’s understanding of the distinction between cyborg and robot, making us far too familiar with the idea of the cyborg displayed as an apocalyptic scene where robots have developed beyond our control, or become intelligent and emotionally aware to the point where they seek dominance over their creator. These depictions are actually of highly developed machines that resemble human beings, as opposed to the ‘hybrid’ cyborg entities that will be explored in this paper. When examining this common narrative in science fiction movies, Goodall explains that they ultimately end in putting “biological humanity on the road to extinction” (Goodall, 2005, p. 1). These narratives have instilled widespread anxiety about robots taking our jobs, but as Fox illustrates, “debates about the future of society are flawed if they focus more upon robots than cyborgs” (Fox, 2018, p. 1). Fox imagines a society where it is the acceptance of humans becoming cyborgs that allows us not to be completely replaced by robots. As Hunt suggests,

“The cyborg is a sign which is all too often forced to signify one thing or another, most commonly the end of humanity or similar apocalyptic scenes. But the cyborg and alternate forms of hybrid beings in themselves do not signify such outcomes. This is why artistic visions and dreams of cyborg existences that escape tyrannical forces of signification provide an invaluable medium in which the sign of the cyborg can rebel (Hunt, 2015, p. 72).”

In order to understand the development of the cyborg through these artistic depictions, we must first understand what a cyborg actually is. Donna Haraway defines the cyborg in her Cyborg Manifesto, as “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” (Haraway, 1991, p. 149). The cyborg is similarly defined by Hunt, however, she states that “the term covers a wide spectrum of interconnections and fusions between the human body, the human psyche, and technological bodies” (Hunt, 2015. p. 5). In her paper I, Cyborg, Pearlman illustrates that there are three basic categories that cyborgs can be grouped into, there are “those that use mechanical elements” (eg. prosthetics), “those that use electronic elements”, (eg. prosthetics with the addition of electronics) and “those that use cybernetics as part of their body”, (eg. implants applied to the organism). These categories are “not fixed and can easily overlap” (Pearlmann, 2015, p. 84). In order to understand the vastness of cyborg forms, the artists we will be exploring each encapsulate one of these categories.

The discussion about the genesis of the cyborg must begin by acknowledging its roots in Greek and Roman mythological hybrid entities, known as chimeras (usually depicted as a fire-breathing female monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail). Hunt recognises that in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the chimeric figure experienced a technologic-mechanic recasting, which manifested in the form of the cyborg (Hunt, 2015, p. 5). This meant that these hybrid entities could now be thought of as fusions between human and machine, as opposed to the animal hybrids seen in the chimeras earliest depictions.

Fig. 1. Reconstructing the Crippled Soldier, McMurtrie, 1918.

The effects of the first world war revealed the frailty of the human body, and began a discourse surrounding the need for it to be improved upon. These new hybrid forms began to enter reality with an emergence of prosthetic limbs mimicking workforce tools in an effort to return wounded soldiers to the workforce (Fig. 1). During this time, due to the exponential development of technology, the idea of the cyborg began to develop a rich complexity. As Hunt illustrates, this merging of humans with machinery began to “call into question the definition of ‘human’ and its relation to the external world” (Hunt, 2015, p. 5).

The decision to create prosthetic limbs, that would give wounded soldiers the ability to be more productive than they were with their biological limbs, inspired many depictions of the cyborg in art, giving people the ability to look to the future and think about ways in which we can improve upon the human body. Both productivity and dissatisfaction with the human mind and body can be seen as the original driving forces in the development of the figure of the cyborg.

These developments heavily influenced the work of one particular art movement, known as Dadaism. The Dada movement produced work that was in protest against what they saw as a senseless war that had happened as a result of a society that made decisions influenced too much by emotion. Hunt explains that “after the destruction of World War I, the cyborg in art emerged as a figure that embodied hopes and utopian futures” (Hunt, 2015, p. 10). The Dadaists’ artwork communicated a desire for a society that acted with more mechanical, and less emotional reasoning. In Blumberg’s view, the Dadaists formed a critique of their society by “creating provocative works that questioned capitalism and conformity, which they believed to be the fundamental motivations for the war” (Blumberg, 2014, n.p.). As Biro illustrates in his book, The Dada Cyborg, the Dada movement and its strategies have been “acknowledged primarily not for their subject matter, but rather for the transformative effect they had on the viewer” (Biro, 2007, p. 26). By using the image of the cyborg as a means of imagining utopian futures and confronting their viewers with the potential effects of technological advancements, the Dadaist’s work evoked an introspective rethinking of what it means to be human. In Hunt’s view, these “hybrid and cyborg entities helped the Dada artists to grapple with the ambiguity and multivalence of their new reality – a world of technological advances” (Hunt, 2015, p. 9). Cyborg imagery became a sign of hope for the Dadaists, and a medium in which to imagine new modes of living post-war.

Dada artist Raoul Hausmann’s work acts as a catalyst in which to understand the genesis of the cyborg within art, exemplifying how new human futures were being explored in the early 20th century, and how art can be used to examine and critique technology and its effect on human evolution. Hausmann, among other Dada artists of his time, developed the process of ‘photomontage’. Hunt explains that while the Dadaists “literally combined images to create organic-technological hybrids”, the cyborg “more generally encompassed the idea of hybrid identity essential for understanding how new forms of existence and society were envisioned post-war” (Hunt, 2015, p. 10). Using imagery from mass-media sources, they evoked reflection upon technology within their society by imagining ways in which humans could potentially merge with machines. This construction of cyborg imagery through text and images would function as a form of constructing possible futures. Hunt explains that,

“Dadaism was, at its core, a manifestation of and reflection on new technological modes of being. As an artistic movement, Dadaism functioned as a critical carrier of cultural information, indicating a seismic shift in the way technology permeated and fundamentally altered the human conception of the self – in short, our ontology (Hunt, 2015, p. 7).”

Fig. 2. Raoul Hausmann, Tatlin Lives at Home, 1920. Photomontage, 40.9 x 27.9 cm. Stockholm: Moderna Museet. Photo: 2007 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Hausmann’s famous photomontage Tatlin Lives At Home (Fig. 2) is an example of how these artists created cyborg entities to demonstrate this shift in our ontology. The relationship between technology, society and human identity is explored through the assembling and remixing of images of the human body and machines. By swapping out the brain for a strange mechanical mechanism, Hausmann illustrates the first category of a cyborg, one that uses mechanical parts, communicating the Dadaists desire for a peaceful society, one in which the mind only makes rational and reasoned decisions. As Biro explains, Tatlin Lives At Home presents “allegorical representations” of the cyborg, to “disrupt reality in an effort to imagine new modes of existence” (Biro, 2007, p. 44). Photomontage became a medium in which Hausmann could merge images from many different sources in order to “project his utopian hopes and fantasies” (Biro, 2009, p. 1). Tatlin Lives At Home utilises the cut and paste aspect of photomontage to “shatter reality into a multiplicity of disconnected fragments”, allowing the re-assembling of these fragments to create “new forms of hybrid identity better able to exist in the modern world” (Biro, 2007, p. 45). This work allowed Hausmann’s viewers to see these depictions as a way of literally breaking down what it means to be human, in order to rebuild our idea of humanity, only now, inclusive of elements of technology and mechanical parts. Hausmann saw this to be the solution to preventing catastrophic events such as the war.

By Dada artists such as Hausmann envisioning cyborg entities, they “hoped to influence this figure’s development, encouraging the forms that they found beneficial and attacking the other types that they believed were highly destructive” (Biro, 2009, p. 64). By using technology as a conceptual theme in his work, and envisioning ways in which we could benefit from the addition of machinery to our bodies, Hausmann begins a discourse surrounding the ways in which we could harness the power of technology to control our evolution. Biro explains that Hausmann’s cyborgs “implied that technological augmentation carried both extreme benefits and extreme risks” (Biro, 2007, p. 31). He provokes us to imagine our own futures involving technology, and think about what elements of this way of living makes us uncomfortable, or that we’d like to leave behind. Hausmann’s photomontages create “testimonials to what could be”, as well as offering “alternatives that highlight weaknesses within existing normality” (Dunne and Raby, 2013, p. 34-35). In this case, Hausmann’s work highlighted the frailty of the human body, as well as our minds. Tatlin Lives at Home shows us that by breaking down our idea of what it means to be human, it is possible to rebuild ourselves into beings who are capable of coexisting with technology.

According to Biro, the Dada artists were oftentimes making work about subjects that didn’t even exist yet (Biro, 2007, p. 27). Hunt informs us that the term ‘cyborg’ wasn’t actually part of the Dada artists vocabulary at this point, although it “aptly captures Dadaists reconceptualization of embodiment and the interconnections they saw rapidly emerging between humans and technology” (Hunt, 2015, p. 9). Unbeknownst to Hausmann, these ideas would become vital in the ever-changing climate of rapid technological advancements, and would actually go on to form the basis of what is considered transhumanist ideology today. As defined by Mark O’ Connell in his book To Be A Machine, the transhumanism worldview is a “conception of our minds and bodies as obsolete technologies, outmoded formats in need of complete overhaul” (O’ Connell, 2017, p. 11). Hausmann and his contemporaries explored and experimented with the redesigning of the human body and the ways in which we can actually enact this ‘overhaul’. By taking on this role, the Dadaists can be characterised as “artistic pioneers of an investigation into ‘the self’ and the parallel reconceptualization of human identity in the early 20th century” (Hunt, 2015, p. 8).

Through the promotion of a re-examination of human identity, Dada artists in Berlin during the early 20th century used cyborg imagery to provide “an invaluable strategy for reading the world and confronting its emerging changes” (Hunt, 2015, p. 15). It was precisely this dedication by artists such as Hausmann, to create work that is an expression of their society’s most vital concerns, that “triggered an investigation of the discordant concepts of self and society” (Hunt, 2015, pg 11). Hausmann’s visions of human-machine hybrids can be seen as some of the first portrayals of how humans may benefit from the addition of machinery to the body. This aptly marks the genesis of cyborg entities in art and paves the way for many more artistic depictions of human advancement through technology and the imagining of hybrid forms and new realities.

Chapter 2: Demonstrating The Cyborg Through Performance

In his paper, Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution, Fukuyama argues that if developments in cybernetics3 and biotechnologies4 are left unchecked, there could be catastrophic consequences for humanity. This highlights the essential role of criticality when exploring such developments. As Fukuyama illustrates, there are two solutions to this problem, the first being to “forbid the use of biotechnology to enhance human characteristics and decline to compete in this dimension”, which is quickly discarded as an option, due to the attractiveness of such enhancements and the complications that would arise in preventing them. Fukuyama concludes that “a second possibility opens up, which is to use that same technology to rise up from the bottom” (Fukuyama, 2002, p. 11). This chapter will examine the work of Australian performance artist Stelarc, and will use his practice as a catalyst for understanding the experimentation phase in the development of the cyborg. Stelarc’s practice illustrates how exploring advancements in technology through performance can help us envision new modes of being, so that technology “remains man’s servant rather than his master” (Fukuyama, 2002, p. 1).

If the Dadaists were at the forefront of imagining these utopian hopes and futures, then Stelarc could be said to be at the forefront of actually experimenting with ideas surrounding the human body’s ability to merge with machines. Advances in technology spanning 60 years, (from the Dadaists in the 1920s to Stelarc in the 1980s), would make it possible for the imagining of cyborg entities to enter reality. Hausmann conceptualised ideas that Stelarc could now manifest. By utilising emerging technology, Stelarc’s artistic practice explores its ability to control the evolution of the human body and how these technologies may prevent our obsolescence. Kroker and Kroker believe that “in a dramatic instance of art as a precession of reality, we are living in a world whose main scientific and technological features have been accurately forecast and artistically performed by Stelarc” (Kroker & Kroker, 2005, p. 63). This chapter will examine how Stelarc’s practice brought Hausmann’s concepts into real-life experiments and how they continue to map the development of the cyborg by adding to the discussion of ways in which we can extrapolate and imagine new futures for humanity through the use of technology.

Stelarc’s Third Hand performance (Fig. 3), completed in 1980, illustrates one of the many ways in which he has developed upon the Dadaists’ reimagining of the human body. This performance explores the augmentation of his body by extending its capabilities, and is a perfect example for looking at the second category of a cyborg, one that uses electronic elements. This prosthetic resembles a third hand and is capable of picking up electric signals from different muscles around the body and sending them to a switching system device on the mechanical third hand in order to give it commands. By exploring the passing over of agency of one’s body to another source, this performance raises important questions around who will have the agency to control our bodies, if these technologically advanced prosthetics were to become our reality.

Fig. 3. Third Hand, Tokyo, Nagoya, Yokohama, 1980. Photo by Simon Hunter.

Stelarc explains that Third Hand has become a “body of work that explores the intimate interface of technology and prosthetic augmentation - not as a replacement but rather as an addition to the body. A prosthesis not as a sign of lack, but rather a symptom of excess” (Stelarc, 2022, n.p.). Similar to the wounded soldier’s prosthetics, Stelarc’s Third Hand is not an attempt to substitute something that is missing, but to give the body new abilities that were previously unattainable. In doing so, Stelarc “probes our anxiety over maintaining a “pure” body and questions whether such a concept still even exists or carries meaning” (Hunt, 2015, p. 71). The addition of prosthetics and technology to the body calls into question what it means to be human, and questions how much more or less human we may become when we merge with machines.

Stelarc believes that “it is only when the body becomes aware of its present predicament that it can map its post-evolutionary strategies” (Stelarc, 1991, p. 591). This claim by Stelarc signifies that we must accept the dissatisfaction with the human body in order to reimagine new modes of being that will prepare us for the future. Third Hand can be seen as one of these post-evolutionary strategies that enable us to move away from this “fear of obsolescence”, of what Goodall writes as “being the losing species in the competition for progress through adaptive advantage” (Goodall, 2005, p. 2). Stelarc’s work allows the cyborg to ‘rebel’ against the prototypical narrative presented to us within pop-culture, demonstrating the incredible ways in which technological developments can prepare us for the future, as well as highlighting the complications that may come along with them. Hunt explains that Stelarc “employs this technological power in order to explore how we might quell our anxieties of hybrid beings and nonhuman others, instead envisioning pleasure in their existence” (Hunt, 2015, p. 71). Through his artistic practice, and performances such as Third Hand, Stelarc depicts ways in which we can use technology to augment and improve upon the human body, ultimately signifying a changing narrative from robots taking over the world to one where we could live harmoniously alongside technology.

Garoian & Gaudelius, in their paper Cyborg Pedagogy, speak of performance art as having the ability to provide artists with “a public arena within which to re-claim and re-present their bodies” (Garoian & Gaudelius, 2001, p. 335). This indicates that art can become a space in which to experiment, a space in which there is room for trial and error, failures and glitches. As Legacy Russel states, “via the cyborgian turn, the artist intentionally embodies error” (Russel, 2020, p. 45). It is this free-thinking ‘public arena’ and the confidence to embody errors that allows Stelarc to come to conclusions otherwise perhaps intangible, had a rigid set of instructions and desired outcomes been put in place, as they would in scientific experiments. Stelarc speaks of this distinction between scientific and artistic research in a talk given at Curtin University when he states that;

“As artists, we’re not interested necessarily in doing methodical scientific research for immediate utilitarian use but rather generating contestable futures, contestable possibilities that might be examined, possibly appropriated, often discarded, but that contribute to that discussion and that interrogation of what it means to be human (Stelarc, 2014).”

Further influencing modern-day transhumanist thought, Stelarc is preoccupied with finding ways in which we can prevent the obsolescence of the human body (Goodall, 2005, p. 1). Much of what drives Stelarc’s practice is the view of the body as being frail and having a vulnerability attached to the idea of being human, as he believes that “the body is neither a very efficient nor a very durable structure, it malfunctions often and fatigues quickly” (Stelarc, 1991, p. 591). Stelarc’s performances can be seen as a series of explorations into how we can improve upon the human body by envisioning it to be more durable and more able to perform for long periods of time, ultimately for it to be more capable than it currently is. It’s evident that this thinking has influenced transhumanist ideology as O’Connell writes that “the underlying premise of transhumanism, after all, was that we all needed fixing, that we were all, by virtue of having human bodies in the first place, disabled” (O, Connell, 2017, p. 215). By thinking about the body as being a kind of structure or architecture, Stelarc explores ways that the addition of technology to the body can allow it to extend its original capabilities, as he sees the body “not as a subject but as an object - not as an object of desire but as an object for designing” (Stelarc, 1991, p. 591). This allows us to recognise that productivity and dissatisfaction with the body’s abilities continue to be the incentive for the development of the cyborg into the late 20th century. O’Connell writes with regard to the transhumanists desires, that these explorations are in an effort to “become better versions of the devices that we were: more efficient, more powerful, more useful” (O, Connell, 2017, p. 5). Stelarc’s explorations surrounding such developments are extremely important in furthering society’s understanding and acceptance of them. By confronting us with the capabilities of these advancements, and the potential realities that they may make possible, Stelarc’s work allows us to question what the essence of humanity is and how much we want technology to change the course of our natural evolution.

With regards to his work with the Alternate Anatomies Lab (AAL), Stelarc speaks about how technology fundamentally determines what it means to be human and how it “is determined historically, culturally and by the technology that is available” (Stelarc, 2014). O’Connell illustrates how this thinking is core to transhumanist ideology as they believe that “our future is predicated in large part on what we might accomplish through our machines” (O’ Connell, 2017, p. 6). This point is reiterated by Richter when he writes that “art in its execution and direction is dependent on the time in which it lives” (Richter, H. 1985. p. 104). This idea intensifies the importance of experimenting with these technologies in order to understand their capabilities, and ultimately as a form of furthering our understanding of ourselves.

Where Hausmann’s photomontages formed the blueprints for ways in which the human body could merge with machines, Stelarc’s performances began to lay down the foundation for ways in which the human body might extend its biological capabilities, giving us the opportunity to explore the elements of his work that make the viewer feel uncomfortable or untrustworthy of the technologies he is using. As stated by Hunt, the “use of cyborg and hybrid identity plays a crucial role in renegotiating the space of the human body and forming a new subjectivity” (Hunt, 2015, p. 15). Stelarc’s work allows us to see ways in which we can use these new technologies in order to prepare us for the future, and does precisely what Dunne and Raby say is essential to any critical design, as it can be seen as an “expression or manifestation of our sceptical fascination with technology, a way of unpicking the different hopes, fears, promises, delusions, and nightmares of technological development and change” (Dunne and Raby, 2013, p. 35). Stelarc’s practice explores and experiments with the redesigning of the human body and proposes ways in which we can prevent our bodies from becoming obsolete. These investigations into the capabilities of a technologically advanced human body open up avenues for us to imagine what we want our future to look like. By exploring ways in which the body can be redesigned, Stelarc believes that “the artist can become an evolutionary guide, extrapolating new trajectories; a genetic sculptor, restructuring and hypersensitizing the human body” (Stelarc cited by Hunt, 2015, p. 71). Using physical technology in his performances, Stelarc gives us the ability to form our own speculations of the future of the human body and how we may merge with such technology, fundamentally changing the perception of what it means to be human.

Chapter 3: Evolving Perception Through Cyborg Embodiment

This final chapter will look at the implementation phase in the development of the cyborg by examining the work of Moon Ribas, a Spanish artist, dancer and choreographer. Demonstrating the third category of a cyborg, her practice focuses not on the bionic body, but on the extension of our senses through cybernetics. Ribas co-founded the Cyborg Foundation in 2010 with fellow cyborg Neil Harbisson, which essentially “helps people become cyborgs; by extending their senses by applying cybernetics to the organism”, they also work to “defend cyborg rights and promote the use of cybernetics in the arts” (Cyborg Foundation, 2020, n.p.). They were inspired to do this after they discovered that there were “no special clinics where physicians and computer scientists could collaborate on devices and develop new ideas together” (Pearlman, 2015, p. 89). Over the last 12 years, Ribas and Harbisson have inspired and helped people to find a way to perceive new senses or repair lost ones, influencing the acceptance of the idea of becoming a cyborg. By examining the work of the Cyborg Foundation and taking an in-depth look at one of Ribas cyborg performances, this chapter will explore how Ribas is developing the public’s understanding of the biotechnology revolution by giving them the tools and knowledge to imagine their own post-evolutionary modes of living. Ribas plays a crucial role in mapping the current developments in the evolution of the cyborg.

Fig. 4. Moon Ribas, Waiting For Earthquakes at Hyphen Hub, 2014. Photo by Ellen Pearlman.

The work by Ribas that this paper will focus on is her performance Waiting For Earthquakes (Fig. 4), which is made possible by the fact that she has implanted seismic sensors in her arms, that are connected to a global seismograph, and can indicate to her when there is an earthquake happening anywhere in the world. If her sensors pick up seismic activity, they can also inform her of the location of the earthquake. Pearlman explains that “during the performance, the exact place the quake is taking place is shown, and its intensity projects on a screen behind her, along with the current location, date, and time” (Pearlman, 2015, p. 88). Similar to some of Stelarc’s performances, Ribas explores the passing over of agency of her body to cybernetics, and artistically performs the outcomes, as she allows the vibrations to influence the movement of her body. This allows the viewer to consider “the possibility of the human body acting as a conduit for data collected from external, natural forces” (Tokareva, 2016, n.p.). What this performance explores is the use of technology as an extension of human perception and the ways in which we can use technology to bring us closer to nature, rather than the role that many modern technologies play in alienating us from it and each other. Rather than trying to change the environment around us, Ribas performances explore ways in which our bodies can be made more capable of living in our ever-changing climate. Ribas and many other members of the Cyborg Foundation have developed interesting ways in which we can reconnect with nature in this way, some having implanted technology that acts as a compass, allowing them the ability to tell their direction in the world, eliminating their reliance on navigation technology such as Google Maps.

Developments in nanotechnology5 have meant that technologies are getting smaller and smaller, so they no longer need to be outside of us, but will become part of the make-up of who we are. Garoian & Gaudelius argue that “performance art enables us to use the cyborg metaphor to create personal narratives of identity as both a strategy of resistance and as a means through which to construct new ideas, images, and myths about ourselves living in a technological world (Garoian, & Gaudelius, 2001, p. 337). It seems that much of the inspiration for these new senses comes from the abilities of animals, with other cyborgs having abilities such as night vision, echolocation, infrared and ultraviolet vision, as well as electric, seismic and magnetic senses. This gives these people the ability to perceive the invisible, and thus begins to change the ways in which they look at and utilise the world around them. The Cyborg Foundation aims to challenge the public’s perception that technology can only alienate us from nature, and to show people that it can be used to gain a deeper understanding of nature and feel more connected to our planet.

The effects of WW1 gave rise to the first wave of discussion into the ethics of human advancement, where society became extremely concerned about its effects on humanity and the human body. It is now apparent that we are in the second wave of such discussions deeming what is ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’, ‘human’ and ‘non-human’, and there seems to be a wider acceptance this time around. But as pointed out by Garoian and Gaudelius, there is still a disparity between why some technologies are commonly accepted and others are not, as they examine how normalized implants are when being used on sick bodies as opposed to the great sense of disgust when it comes to implants in healthy bodies.

“In the healthy body such prosthetics become the marker of abjection, the non-human. This difference in the value that we assign to such devices is of critical importance for it renders the cyborg body as harmless when its purpose is to restore the semblance of lost humanity, but as monstrous when the body is healthy (Garoian & Gaudelius, 2001, p. 336).”