Glitch, The Aesthetic Of Failure

“Tactical Media are what happens when the cheap 'do it yourself' media, made possible by the revolution in consumer electronics and expanded forms of distribution (from public access cable to the internet) are exploited by groups and individuals who feel aggrieved by or excluded from the wider culture. Awareness of this tactical/strategic dichotomy helped us to name a class of producers who seem uniquely aware of the value of these temporary reversals in the flow of power. And rather than resisting these rebellions, do everything in their power to amplify them. We dubbed their (our) work tactical media.” (Garcia, D. and Lovink, G. 1997).

Glitch is understood to be the study of the politics and aesthetics of failures. As technology becomes more user-friendly, the interfaces and systems we use become harder to understand. Far too often we are unaware of the complexity of the system's that we use everyday, eg. phones, tablets, computers, screens, video games, etc. As a form of tactical media, artists and activists have used glitch by introducing a deliberate malfunction to a system, as an experiment to understand how the system will react. “Some artists set out to elucidate and deconstruct the hierarchies of these systems of assemblage.” (Menkman, R. 2009/2010, p. 3). By doing so, the artist makes the audience more aware that these systems and interfaces are layered, thus making the politics of this layering more visible to us. Rosa Menkman, who has written extensively on this subject, describes that “The quest for complete transparency has changed the computer system into a highly complex assemblage that is often hard to penetrate and sometimes even completely closed off.” (Menkman, R. 2009/2010, p. 3).

Glitches can present themselves in many different ways, such as a technological glitch, an energy glitch, a political glitch etc. I will guide you through how artists and musicians have used glitch in different ways to produce work and show that we shouldn't be fighting the inevitable fact that things will break and malfunction.

Rather, understanding that glitch can be used to aid creation, and that failures in systems actually allow us to understand them better. “It is failure that guides evolution; perfection offers no incentive for improvement.” (Whitehead, C. 1999). This essay will express how the tactic of glitch can be used across music, art, and politics. I will focus on glitch used through manual manipulation of CD’s in Yasunao Tone’s ‘Wounded CD’, through video game modification in Cory Arcangel’s ‘Super Mario Clouds’ and Rosa Menkman’s, ‘A Vernacular of File Formats’, where she looks at how glitch can be used a political tool.

Yasunao Tone’s ‘Wounded CD’

Luigi Russolo’s mechanical noise generators and his Futurist manifesto ‘The Art of Noises’, published in 1913, marks the beginning of the glitch aesthetic, but it wasn't until the later half of the 20th century that people like Yasunao Tone started manipulating the audio media manually. (Stuart, C. 2003, p. 47). Tone would “create

work based on the damaged sound of the distressed CD player as it tries to cope with the loss of binary information”. (Stuart, C. 2003, p. 47). For his piece ‘Wounded CD’, Tone placed small bits of semi-transparent tape onto the CD to interrupt the reading of the audio information. This kind of manual tampering with devices was an extremely new form of making music at the time. Tone was involved with experimental Fluxus Group Ongaku where they experimented and expanded on sound studies. “Subsequent to Cage's low-fi phonograph experiments, a number of Fluxus musicians also engaged in destructive sound expansion practices, destroying

a number of traditional instruments, as well as turntables and records.” (Stuart, C. 2003, p. 47). Group Ongaku (Music Group) not only disrupted the idea of classical music but shattered its conventions and paved the way for an enormous amount of alternative modes of expression.

“Believe it or not, classical music has been the springboard for an enormous amount of radical innovation in the performing and visual arts. Representing the political and social superstructure of "high culture", rigid instrumentation and traditional compositions of orchestral music have repeatedly been the target for a creative class seeking to shatter conventions and shape new modes of expression. Composers assembled and deconstructed nearly every aspect of music in a conscious attempt to redefine musical arrangements from within the medium.” (Gates, J, 2017).

Fig. 1. Yasunao Tone

From the very beginning of the CD player as a medium, David Ranada, who worked for Stereo Review magazine, sought ways to test the system for himself. For his first feature on CDs, he worked out a way to make a CD jump and skip. Ranada had a huge role to play in informing people about the capabilities of these CD players. (Stuart, C. 2003, p. 48).

Yasunao Tone’s ‘Wounded CD’ can be traced back to this finding. “Tone had read that digital recording has almost no noise and produces sound very faithful to the original, but when it misreads 1 with 0, it makes very strange sounds due to the binary code becoming a totally different numerical value.” (Stuart, C. 2003, p. 48).

Tone wasn’t afraid of failure while creating this piece, instead he was deliberately looking for ways to manipulate the CD player in order to achieve new sounds. “Ranada found by poking around in the circuitry that he could read exactly how many errors were being concealed and realized that error correction was itself erratic and would often deal with large errors in different ways from playing to playing. This became important for future uses of the technology, especially for those musicians who push the system in an attempt to draw out the accidental and unforeseen from the device.” (Stuart, C. 2003, p. 48).

Neither Tone nor his audience would know what a performance was going to sound like until it was over, and if they came to another one of his performances, it would be totally different again. Tone recounts: “I had many trials and errors. I was pleased with the result, because the CD player behaved frantically and out of control. It was a perfect device for performance.” (Stuart, C. 2003, p. 48). This extended the performance possibilities for Tone in many ways as the sounds that were created from the shuttering disc were constantly changing. Glitch has an inherent critical moment(um), meaning that any glitch has the potential to modulate or productively

damage the norms of techno-culture, in the moment at which its potential is first grasped. (Menkman, 2011, p. 8). Tone’s ‘Wounded CD’ was a result of him seeing the potential for something and grasping it, thus breaking down the norms of classical music and paving the way for the next generation of creative thinkers.

Cory Arcangel’s ‘Super Mario Clouds’

“I write my own software, and my work is often based on obsolete hardware. This way, I try to avoid the oppressive censoring process that modern software and hardware configurations dictate. By writing my own software I can have control over every aesthetic decision, and by writing for computers that are sometimes 15-20 years old, I can be assured that the simplified architecture of these machines will provide me with a freedom for artistic expression that is often concealed in the user-friendly aperitifs of modern computing tools.” (Arcangel, C . 2001, p. 523).

Arcangel engages in video game modification, which is a prime example of how glitch can be used in an art practice. His work approaches glitch as a practice of opening up the ‘black box’ of contemporary electronics and protocols. “The inner workings of the device are unknown to the user, with the circuitry of the device like a mysterious “black box” that is irrelevant to using it.” (Hertz, G and Parikka, J. 2012, p. 428). I will discuss Cory Arcangel’s piece ‘Super Mario Clouds’ where he modified an NES (Nintendo Entertainment System) to erase everything but the clouds from a Super Mario Bros videogame. “The work was created on the basis of a manipulation of the hardware and software. Cory Arcangel had to open the cartridge, on which the game was stored, and replace the Nintendo graphics chip with a chip on which he had burned a program he had written himself.” (Baumgärtel, T.)

In an artist statement, Arcangel mentions that “Exponentially growing options do not necessarily represent artistic progress or greater potential. In fact, they might do quite the opposite: mediocrity may stem from user-friendliness.” (Arcangel, C. 2001, p. 523). What Arcangel is touching on here is that by making these interfaces easier for us to use, it requires far less understanding from us, as users, as to how these systems actually work. “As Bruno Latooue notes, it is often when things break down that a seemingly inert system opens up to reveal that its objects contain more objects, and actually those numerous objects are composed of relations, histories and contingencies.” (Hertz, G and Parikka, J. 2012, p. 428). Arcangel’s choice to modify this seemingly outdated game gives room for us to think about alternative ways of creating that don’t rely on modern technologies.

“I find that modern software and hardware configurations often dictate a process of presenting the user with limitless options, thereby eliminating the need for invention.” (Arcangel, C. 2001, p. 523).

Fig. 2. Cory Arcangel’s ‘Super Mario Clouds’ installed at the Whitney Art Museum (2002)

Arcangel is an artist who works with obsolete media, also known as ‘zombie media’ which is mainly a result of ‘planned obsolescence’. This was Bernard London’s proposal in 1932 to solve the Great Depression. (Hertz, G and Parikka, J. 2012, p. 425). Not only does Arcangel’s ‘Super Mario Clouds’ push the boundaries of how glitch can be used as an artistic tool, it also plays a part in fighting the ever growing pattern of planned obsolescence.

“In reference to contemporary consumer products, planned obsolescence takes many forms. It is not only an ideology, or a discourse, but more accurately it takes place on a micropolitical level of design: difficult-to-replace batteries in personal MP3 audio players, proprietary cables, and chargers that are only manufactured for a short period ” (Hertz, G and Parikka, J. 2012, p. 426).

“Zombie media is concerned with media that is not only out of use, but resurrected to new uses, contexts and adaptations.” (Hertz, G and Parikka, J. 2012, p. 429). Archangel’s engagement with obsolete technologies instantly adds layers to his work as these technologies have their own purposes and histories in and of themselves. “Media in its various layers embodies memory: not only human memory, but also the memory of things, of objects, of chemicals and of circuits.” (Hertz, G and Parikka, J. 2012, p. 425).

“The elitist discourse of the upgrade is a dogma widely pursued by the naive victims of a persistent upgrade culture. The consumer only has to dial #1-800 to stay on top of the technological curve, the waves of both euphoria and disappointment. It has become normal that in the future a consumer will pay less for a device that can do more. The user has to realize that improving is nothing more than a proprietary protocol, a deluded consumer myth about progression towards a holy grail of perfection.” (Menkman, R. 2009/2010, p. 2).

Arcangel shares, “I like the idea of making things out of trash and the idea of actually having to break into something that I find in the trash even better. The only way to make work for the NES is to hack and solder a cartridge.” (Arcangel, C. 2002). Arcangel’s practice resists the pattern of planned obsolescence by continuing to use old media that would otherwise be discarded, eg. ‘writing for computers that are sometimes 15-20 years old’ (Arcangel, C. 2001, p. 523).

“Network engineers argue that the internetwork was designed ‘to appear seamless. Indeed they were so successful that today’s Internet users probably do not even realize that their messages traverse more than one network.” (Terranova, T. 2004, p. 60).

A practice like Arcangel’s allows us to see ways in which we can challenge this normalised pattern of contemporary media technologies and shows the ability to create something that is completely new and innovative by deliberately introducing glitches to a system such as an NES. Arcangel has published the source code for ‘Super Mario Clouds’ on the WayBack Machine Internet Archive. By doing this, Arcangel has extended the lifespan of this piece of work far beyond his existence and is sharing his knowledge to anyone who seeks to find it. I see Arcangels resistance to planned obsolescence and engagement with open source code as a form of glitch in itself, as he is making the audience aware of the layers that exist in his work.

Rosa Menkman’s ‘A Vernacular of File Formats’

“The fact remains that the doxa about the value, cultural significance, and efficacy of the streets has changed. This is less an objective than a subjective truth, a truth of perception, a general impression of a shared sensibility. It is precisely this change in sensibility that politically engaged new media art projects negotiate. These projects are not oriented toward the grand, sweeping revolutionary event; rather, they engage in a micropolitics of disruption, intervention, and education.” (Raley, R. 2009, p. 1).

Glitch is interested in politics of different media forms - transmissions media, file formats, algorithms, recording and playback equipment. I will use Menkman’s ‘A Vernacular of File Formats’ and her wider practice as a key example of how glitch can be used as a political tool by making political matters visible, and in doing so, communicate with large audiences about the political structures, layers and hierarchies that exist within the highly complex systems of modern media technology. “This system consists of layers of obfuscated protocols that find their origin in ideologies, economies, political hierarchies and social conventions, which are subsequently operated by different actors.” (Menkman, R. 2009/2010, p. 3).

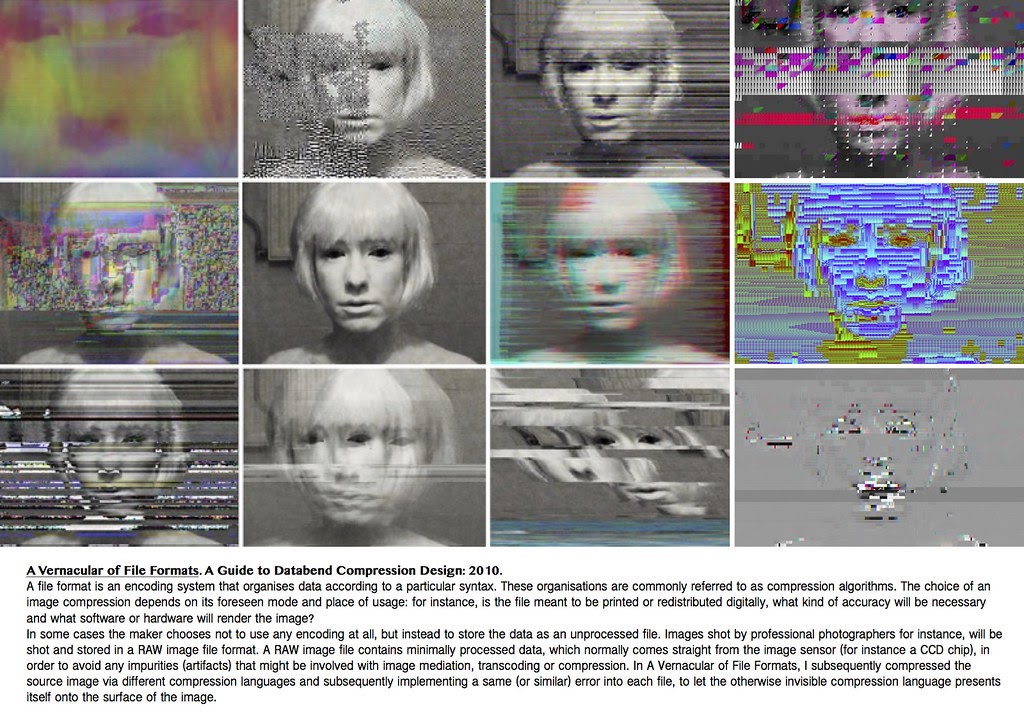

Fig. 3. Rosa Menkman, ‘A Vernacular of File Formats’, 2010.

“The spectator is forced to acknowledge that the use of the computer is based on a genealogy of conventions, while in reality the computer is a machine that can be bent or used in many different ways. With the creation of breaks within politics and social and economical conventions, the audience may become aware of the preprogrammed patterns. Now, a distributed awareness of a new interaction gestalt can take form.” (Menkman, R. 2009/2010, p. 3).

Rosa Menkman is an artist who engages with the micropolitics of glitch through disruption, intervention, and education. In ‘A Vernacular of File Formats’, Menkman looks at the politics of file formats through the modification of images and allows us to see first hand how failure in systems can give us a broader understanding of them. But how is this practice political? Making compression technologies visible allows us to think about the history of their construction and the historical legacy of file formats and image machine visioning systems. “By deviating from the values of the originally recorded image, the image can be displayed in a distorted way and the structure of the file becomes visible.” (Menkman, 2011, p. 18).

“Our critical infrastructure is increasingly computerised and networked, and that brings with it the risk of cyberattacks. We have already seen multiple Russian attacks against the Ukrainian power grid, and Chinese espionage operations against the US and other countries. North Korea has stolen tens of millions of dollars from international banking systems. These risks are only increasing, both from governments and non-state actors.” (Schneider, B. 2018, p. 121)

In her practice, Menkman wants to address issues of shared human concern by researching what is being compromised. “The tension between universality and divergence that informs the open space of internetworking, in fact, produces a rich cultural dynamic and a set of political questions that are taken up again and again across network culture at large.” (Terranova, T. 2004, p. 62). Resolution studies aren't just about what is being solved, but also about the latent space of resolution, the space of many things compromised. Who sets the resolutions? Who makes the compromise? How can we think through compromises, rather than through set solutions? (Menkman, 2020) “I don’t think that failure or glitching necessarily always give us a better understanding of something, but it does give us a mode to unpack what is supposed to work. It’s only by something failing, that we are encouraged to understand how it was supposed to work in the first place.”

(Menkman, 2020)

“The glitch is a wonderful experience of an interruption that shifts an object away from its ordinary form and discourse. For a moment I am shocked, lost and in awe, asking myself what this other utterance is, how it was created. Is it perhaps ...a glitch? But once I named it, the momentum -the glitch- is no more…” (Menkman, R. 2009/2010, p. 5).

This essay has looked at some examples of how artists and musicians use glitch as both a creative tool and a political one. Tone, Arcangel and Menkman’s practices all have their own kind of heuristic value, giving us an insight into the progressive and informative potential of glitch. They show us ways in which glitch can be used to

create a temporary reversal in the flow of power. ( Garcia, D. and Lovink, G. 1997).

Bibliography:

Arcangel, C. (2001). Artists' Statements. Leonardo, 34(5), 523-526.

Accessed on: 24th March 2020

Accessed at: www.jstor.org/stable/1577248

Arcangel, C. (2002). SOURCE CODE

Accessed on: 24th March 2020

Accessed at:

https://web.archive.org/web/20021118090831/http://www.beigerecords.com/cory/21c/21c.html

Baumgärtel, T. Media Art Net

Accessed on: 24th March 2020

Accessed at: http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/super-mario-cloud/

Garcia, D. and Lovink, G. (1997). The ABC of Tactical Media

Accessed at:

https://www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-9705/msg00096.html

Accessed on: 15th March 2020

Griffin, T. (2011). Compression. MIT Press.

Accessed on: March 20, 2020

Accessed at: www.jstor.org/stable/23014848

Raley, R. (2009). Tactical Media. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, MN.

Schneier, B. (2018). ON CYBERSECURITY. Journal of International Affairs.

Accessed at: www.jstor.org/stable/26552335

Accessed on: 6th March 2020

Menkman, R. (2009/2010). Glitch Studies Manifesto. Amsterdam/Cologne.

Menkman (2011). The Glitch Moment(um). Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam.

Menkman (2020). Interview with Rachel O’Dwyer, 30 March.

Stuart, C. (2003). Damaged Sound: Glitching and Skipping Compact Discs in the Audio of Yasunao Tone, Nicolas Collins and Oval. Leonardo Music Journal.

Accessed on: March 20, 2020

Accessed at: www.jstor.org/stable/1513449

Terranova, T (2007). Crisis in Global Economy. Los Angeles. Semiotext(e).

Terranova, T (2004). Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age. Londo and Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto Press

Hertz, G and Parikka, J. (2012). Zombie Media: Circuit Bending Media Archaeolog into an Art Method.

Whitehead, C. (1999). The Intuitionist . Anchor Books. New York.

Fig. 1. Yasunao Tone.

Accessed on: 21st March 2020

Accessed at:

https://dmsp.digital.eca.ed.ac.uk/blog/exploringentropy2014/2014/02/18/yasunaotoneexperiments-with-cds/

Fig. 2. Cory Arcangel’s ‘Super Mario Clouds’ installed at the Whitney Art Museum.

Accessed on: 12th March 2020

Accessed at: https://whitney.org/collection/works/20588

Fig. 3. Rosa Menkman, ‘A Vernacular of File Formats’.

Accessed on: 12th March 2020

Accessed at:

https://sites.google.com/site/newmedianewtechnology2019/portfolios/marissa/1-1-icon